As Boom Supersonic aims to make the world dramatically more accessible by bringing supersonic flight to millions of people around the globe, we reflect on the aviators who broke new ground throughout history to make it possible for everyone to participate in the dream of flight. In honor of Black History Month, we are spotlighting the historic firsts of Black pioneers in aviation and aerospace.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Americans of all races dreamed of flying, but flight schools in the United States would not allow Black students. In order to get pilot training, Black Americans had to travel to Europe to earn their licenses, later opening their own flight training schools to train others. The Tuskegee Airmen, formed during World War II, were the first Black Americans to be trained and serve as military pilots.

From first flights across the United States to breaking barriers in combat, these are some of the flights that changed history, and the pilots who paved the way for the future of flying.

Charles Alfred Anderson

Charles Alfred “Chief” Anderson was an American aviator known as the Father of Black Aviation. Anderson earned the nickname “Chief” as chief flight instructor of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first Black military aviators in the U.S. Armed Forces. The Tuskegee Airmen were active during World War II, at a time when the military was still segregated.

In 1932, Anderson became the first African American to receive an air transport pilot’s license from the Civil Aeronautics Administration.

Recruited in 1940 to serve as the chief flight instructor for a new Army program at the Tuskegee Institute, Anderson developed the pilot training program and taught its first advanced course. In 1941, Anderson took First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt on a flight that is known as “The Flight That Changed History”.

Later that year, Anderson was selected as Tuskegee’s Ground Commander and Chief Instructor for America’s first all-Black fighter squadron, the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

Tuskegee Airmen flew Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, Bell P-39 Airacobras, Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, and North American P-51 Mustangs, outfitted with an iconic red tail, rudder, and nose bands. The 450 Tuskegee Airmen who saw combat in World War II flew 1,378 combat missions and earned over 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, among other distinguished honors, helping bring about the desegregation of the military.

James Banning

James Banning is known as the first African American Pilot to Fly Across America. In the early 1920s, there was not a flying school in America where a Black person could train as a pilot. Banning found an Army aviator who was willing to teach him in 1926, when he became one of the first Black pilots in history.

In 1932, Banning and his mechanic, Thomas C. Allen, set out from a small airport in Los Angeles to make a historical coast-to-coast flight. The pair were known as “The Flying Hoboes”, as the team needed to raise money for the next leg of their trip each time they stopped. The duo made the 3,300 mile trip from Los Angeles to Long Island in 41 hours and 27 minutes of flight time over the course of 21 days.

Only four months later, Banning died in a plane crash at an air show in San Diego.

Bessie Coleman

Bessie Coleman was the first woman of African American and Native American descent to earn her pilot’s license, though she had to travel outside of the United States to get her training. She took French lessons and earned her pilot’s license in France in 1921.

In France, Coleman learned how to perform aerial maneuvers in a Nieuport Type 82 biplane. When she returned to the U.S., she flew in air shows, performing daring stunts such as walking on the wings or parachuting. She advocated for change to segregation laws by refusing to perform at air shows that had segregated entry gates.

Coleman planned to open a flight school so that other Black women could follow in her footsteps and learn to fly. Tragically, she was killed in an accident in 1926 at the age of 34 when her aircraft went into a nose-dive and tailspin during a practice flight.

In 1929, Black aviation enthusiast and entrepreneur William Powell opened the Bessie Coleman Aero Club and the Bessie Coleman Flying School in her honor. Both men and women were permitted to apply, posthumously fulfilling Coleman’s dream of founding a flight school for Black pilots and raising awareness for Black aviation.

Eugene Bullard

Eugene Bullard made history as the first Black American military combat pilot, however it was not in the United States.

When World War I broke out, Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. After becoming a decorated infantryman, he was invited to join the French Air Force and received permission to train as a pilot. In 1917, he flew combat missions with the Lafayette Flying Corps.

Bullard went on to participate in more than 20 combat missions in the first World War.

His military career continued at the age of 46, when he rejoined the French army when the Germans invaded France in 1940. He was one of the veterans chosen to light the ‘Everlasting Flame’ at the French Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe in 1954. In 1959, the French honored him with the Knight of the Legion of Honor.

Cornelius Coffey

Cornelius Coffey is known as the first Black aviator who had both a pilot and mechanic’s license, and the first to found an aviation school.

Coffey was studying to be an auto mechanic in the mid-1920s, but he dreamed of flying and was denied acceptance into flight schools because of his race. He and fellow Black mechanic John Robinson built a one-seat airplane powered by a motorcycle engine and the two taught themselves to fly.

Coffey established the Coffey School of Aeronautics in 1938, teaching both Black and White students, as well as male and female pilots in Illinois. One student was his future wife, famed Black female aviator Willa Brown.

As President of the National Airmen’s Association, Coffey flew from Chicago to Washington, D.C. to advocate for the inclusion of Black pilots in President Roosevelt’s Civilian Pilot Training Program. He met with then-Senator Harry Truman, who would later go on to integrate the armed services during his presidency.

Willa Brown

Willa Brown is remembered as the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license in the U.S. in 1938. She also co-founded the Coffey School of Aeronautics with her husband, Cornelius Coffey. She went on to become the first Black woman to serve as a Civil Air Patrol Officer, as well as the first to receive a commercial pilot’s license and even the first to run for Congress in 1946.

Brown was inspired by the legend of Bessie Coleman and determined to fly. She played a prominent role in her husband Coffey’s Chicago flying club and worked to open up flying to African Americans in the area. She lobbied for desegregation of the military. Under her leadership, the Coffey School of Aeronautics was selected to offer the Civilian Pilot Training Program that paved the way for training the Tuskegee Airmen.

She worked with Coffey on the formation of the National Airmen Association, promoting Black Americans in aviation, and launched the tradition of an annual flyover of Bessie Coleman’s grave in Chicago – a tradition that still exists today.

Marlon Green

The first Black American to become a commercial airline pilot was Marlon Green in 1963.

As a pilot in the Air Force, Green flew the SA-16 Albatross with the 36th Air Rescue Squadron. In 1957, he applied to become a commercial airline pilot with Continental Airlines, applying without checking the box asking for his racial identity. Despite his qualifications, when the airline discovered that he was Black, his application was rejected.

He sued Continental for discrimination, and the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Eventually, in 1963, the court ruled that Green had been unlawfully discriminated against. As a result, he was hired by the airline and flew for them until 1978.

Breaking Barriers

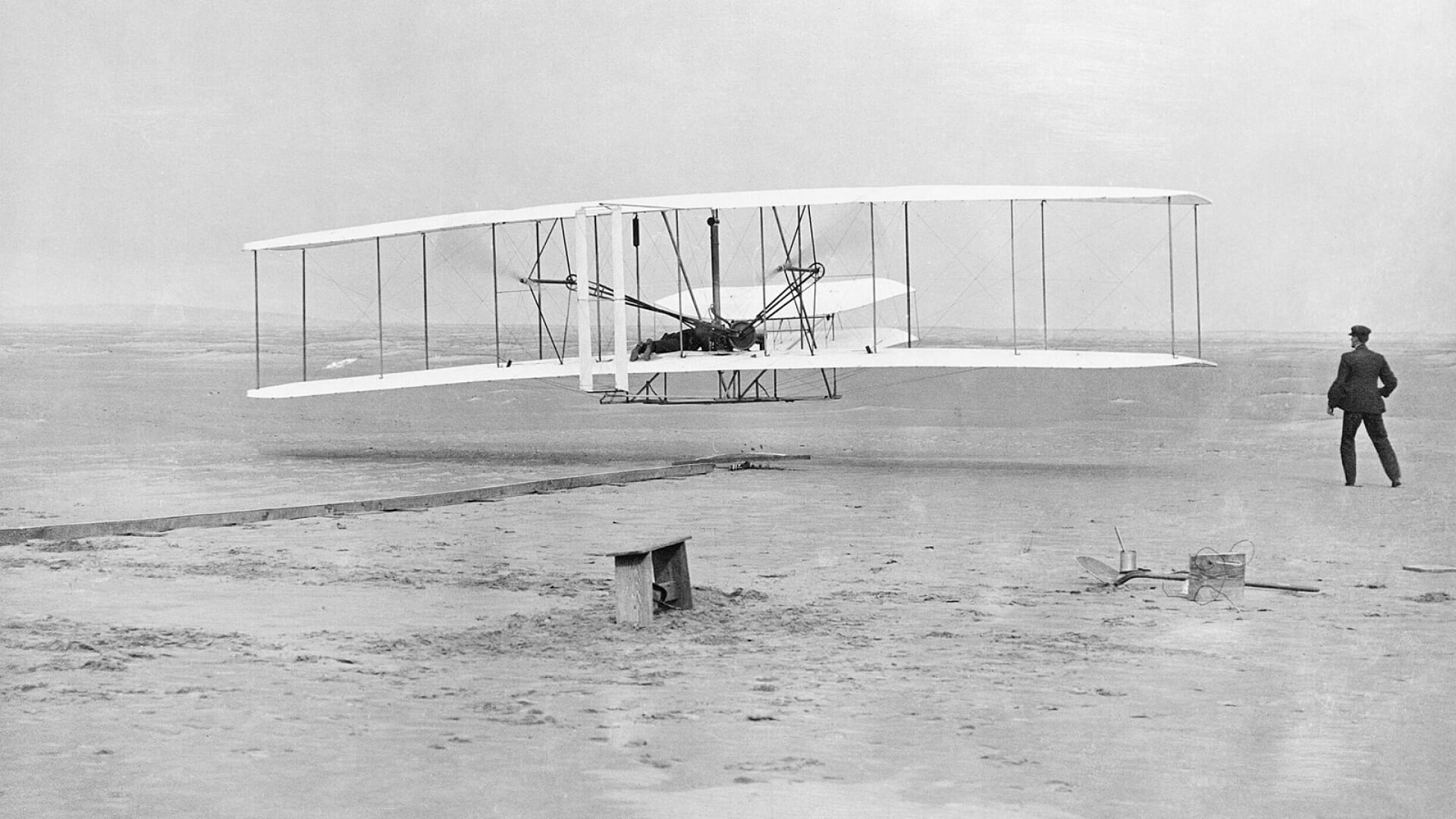

From the moment of first flight, aviation has been shaped by innovators and pioneers who dreamed beyond the limits of the status quo. Advancements in flight have a unique ability to help create a more connected world. We are inspired by the pioneering spirit of these important historical figures, and so many others, who broke barriers to pursue their dreams of flying and changed history.