When an inventor builds a new product, they’re most likely not thinking about the inexorable end of its useful life. The eventual resting place of a product 20 or even 50 years into the future is difficult to imagine. Whether it’s a better light bulb or a safer propane tank, inventors focus on solving a problem and getting a product into the hands of customers rather than its disposal.

For Boom, a product’s entire life cycle is equally important, including its retirement from the market. Boom is building sustainability into every aspect of Overture, its supersonic commercial airliner, including the eventual decommissioning of the aircraft. The team is envisioning a recycling process that may not even begin for 40 years. But, it requires attention and research now.

Boom’s Head of Sustainability and Environment, Raymond Russell, explains the approach: “Because there’s no international standard for recycling many of the materials we’ll use to build Overture, our team is focused on selecting materials that have the highest probability for safe recycling, in addition to weighing critical aspects such as safety and performance. Looking closely at recycling, we’re examining the likelihood of whether a market will exist for those recycled materials in several decades. If we were to recycle Overture today, the supply chain may not support the effort. But in 30 to 40 years from now, that same supply chain should be thriving.”

Recycling gets its start at the junkyard

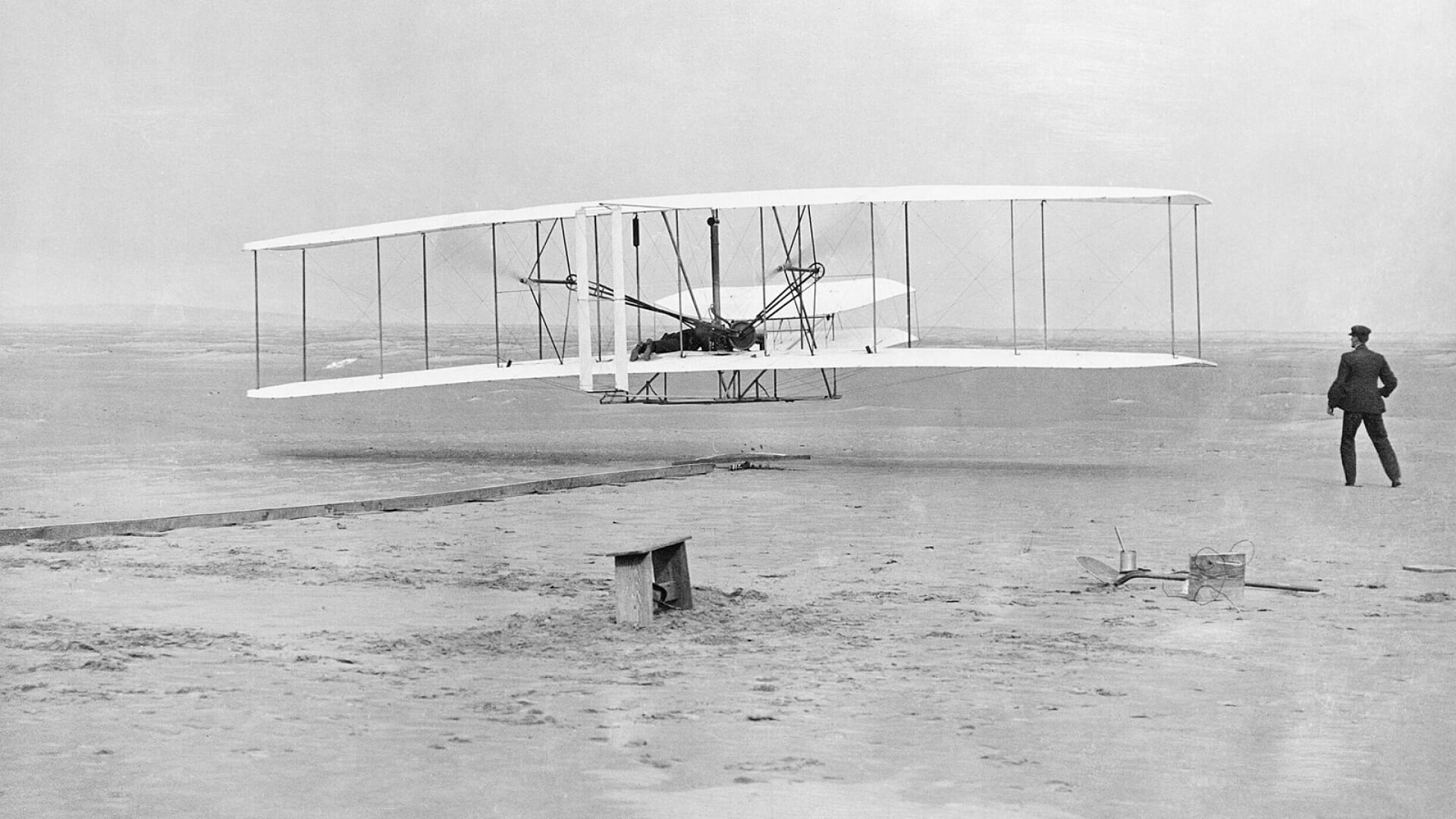

Since 1903 when the Wright Brothers made history flying their first powered aircraft, manufacturers have sought ways to repurpose aircraft parts. Extracting valuable parts from aircraft made economic sense, especially in the early days of aviation when production was limited and parts and materials were scarce.

But repurposing had its dangers. Most aircraft parts should not be reused without inspection and certification, given the risks of structural fatigue and degradation. Until the establishment of an approved inspection process, the prospective buyer had little assurance that parts were safe. That process began in 1926 when the aviation industry asked the U.S. Congress to enact legislation to regulate civil aviation. It would take several decades for a process similar to today’s certification to come into play.

Recycling, as opposed to repurposing, gained momentum in the 1970s. As the market grew, so did the need for standardized and safe disposal methods, as well as research. It wasn’t until the 2000s that Airbus and Tarmac Aerosave established a proven method for decommissioning, dismantling and recycling the entire Airbus aircraft product range in an environmentally responsible way. Through a joint venture, the companies explored all aspects of end-of-life aircraft management, including how best to store aircraft after decommissioning, how to safely dismantle them, and how to ensure materials are effectively recycled. The result was an intense increase in the effectiveness of aircraft recycling. Up to 92% of plane components are now recyclable, a significant improvement on the earlier estimated rate of 70%.

The options for recycling and repurposing continue to grow. A Belgian recycling firm, AeroCircular, is even using decommissioned aircraft to support pilot training. They’re working with Euramec to upcycle end-of-life cockpits and fuselages for flight simulation training, offering a real-life setting to learn the ins and outs of the aircraft.

The lucrative business of aircraft recycling

The aircraft recycling market is expected to reach $8 billion by 2027. But whether aircraft owners can tap into that value when they retire aircraft largely depends on the type of aircraft. Value hinges on whether there is a demand for specific parts, materials and engines. In some cases, the engines are more valuable than the aircraft itself and it’s more profitable to recycle.

“This is when good service records pay off,” said Russell. “If an aircraft owner can demonstrate service records and parts certification, they’ll draw more value from the asset. And because reusable parts can represent close to 90% of a retired aircraft’s value, recyclers reap more value from younger aircraft that are still in service, offering a possible incentive to retire aircraft early.”

COVID-related commercial aircraft retirements also portend a surge in part availability. Pre-pandemic estimates called for more than 12,000 commercial aircraft to be retired in the next 20 years (with a combined value of $1.3 trillion), positioning the aircraft recycling market for continued growth.

“There’s a financial advantage in owning aircraft with long lifespans that will fly for decades,” said Russell. “And, when you integrate recycling into the design and build, you lay the foundation for the safe — and possibly even more financially advantageous — recycling of the aircraft in the decades to come.”

Repurposed parts move from the cabin to conference table

Aircraft interiors represent a unique challenge. While seats and tray tables aren’t deemed hazardous, their composition and materials are often not identifiable. Until the 1980s, recycling codes weren’t widely used and manufacturers did not routinely mark each part of an aircraft interior. Today, new approaches are setting the stage for interiors, and many other parts, to find new lives as practical items. The emphasis on recycling interiors is critical for minimizing landfill contributions as the 15% of decommissioned planes which end in the landfill are mostly cabin interior components.

The Aircraft Interior Recycling Association, which operates a recycling facility that breaks apart interior components, is working with manufacturers to identify every piece of plastic in new aircraft interiors. They currently recycle seat covers into household carpets, as well as other items salvaged from aircraft interiors.

Older parts are also repurposed as art and household items around the world. MotoArt, which repurposes components into furniture, is one of several companies reinventing old machinery. They fashion General Electric engine nacelles into their Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet Conference Table, and airframes of F-80 Shooting Stars into the F-80 Shooting Star Stabilizer Desk.

New materials, new opportunities

Until recently, most aircraft were built with aluminum — a material that’s both easy to recycle and in-demand. But many new aircraft fuselages are built with carbon fiber composites, for which the recycling industry is still nascent.The Aircraft Fleet Recycling Association, a group of manufacturers, airlines, recyclers, and researchers, coordinates research on new disposal methods, and technologies exist now that make such recycling safe and effective. Thanks to these new recycling methods, the global carbon fiber recycling market is projected to grow nearly 80% by 2025.

Boom will be primarily using primarily carbon fiber for Overture’s fuselage, and the company is researching emerging options for recycling the material. “Recycling carbon fiber isn’t as simple as recycling a soda can, which is composed of one material: aluminum,” explains Russell. “Carbon fiber composites include polymers, which must be burned off or chemically dissolved. Another hurdle lies in preserving the integrity of the fibers so they can be refabricated. These are complex technical challenges, but recent advancements assure us that it’s possible.”

Boom’s plans for a safe and effective program to disassemble and decommission Overture will encompass all materials, parts and fluids. Thanks to recycling industry advancements, the tools to recycle and repurpose nearly 100% of Overture are within reach.

“As a new entrant, we are already planning for what will happen to Overture at the end of its useful life — a future that is decades away,” concludes Russell. “By starting to design for recycling early in the program, we can maximize the fraction of Overture that can be recycled or reused.”