“Have I ever told you about Hoot’s Law?” began Captain ‘Hoot’ Gibson, breaking a long and cold silence in NASA’s flight simulator.

Charlie Bolden, Hoot’s close friend, colleague, and copilot for the upcoming 24th mission of NASA’s Space Program, shook his head ‘no.’ He still held in his hands the flight controls of the simulated space shuttle, which as a result of his own mistakes, had just lost two engines and “crashed” into the ocean.

“No, you haven’t,” Bolden continued sheepishly. “What is Hoot’s Law?”

With a wry smile, Hoot placed his hand on Bolden’s shoulder and answered, “No matter how bad things are, you can always make them worse.”

Feeling the size of a pea, Bolden shifted in his seat until Hoot added, “But don’t worry. It happens to the best of us.”

According to Bolden, Hoot was more than a commander for the STS-61-C space shuttle crew. His leadership style was like that of a father figure, as he reminded his team that “deaths” in the simulator were the exact reason why we trained. “Hoot’s Law,” said Hoot, was established not because of Bolden’s error, but because of his own personal mistakes.

Long before Bolden ever crashed the simulator into the ocean, Hoot himself made the simulated mistake of a lifetime:

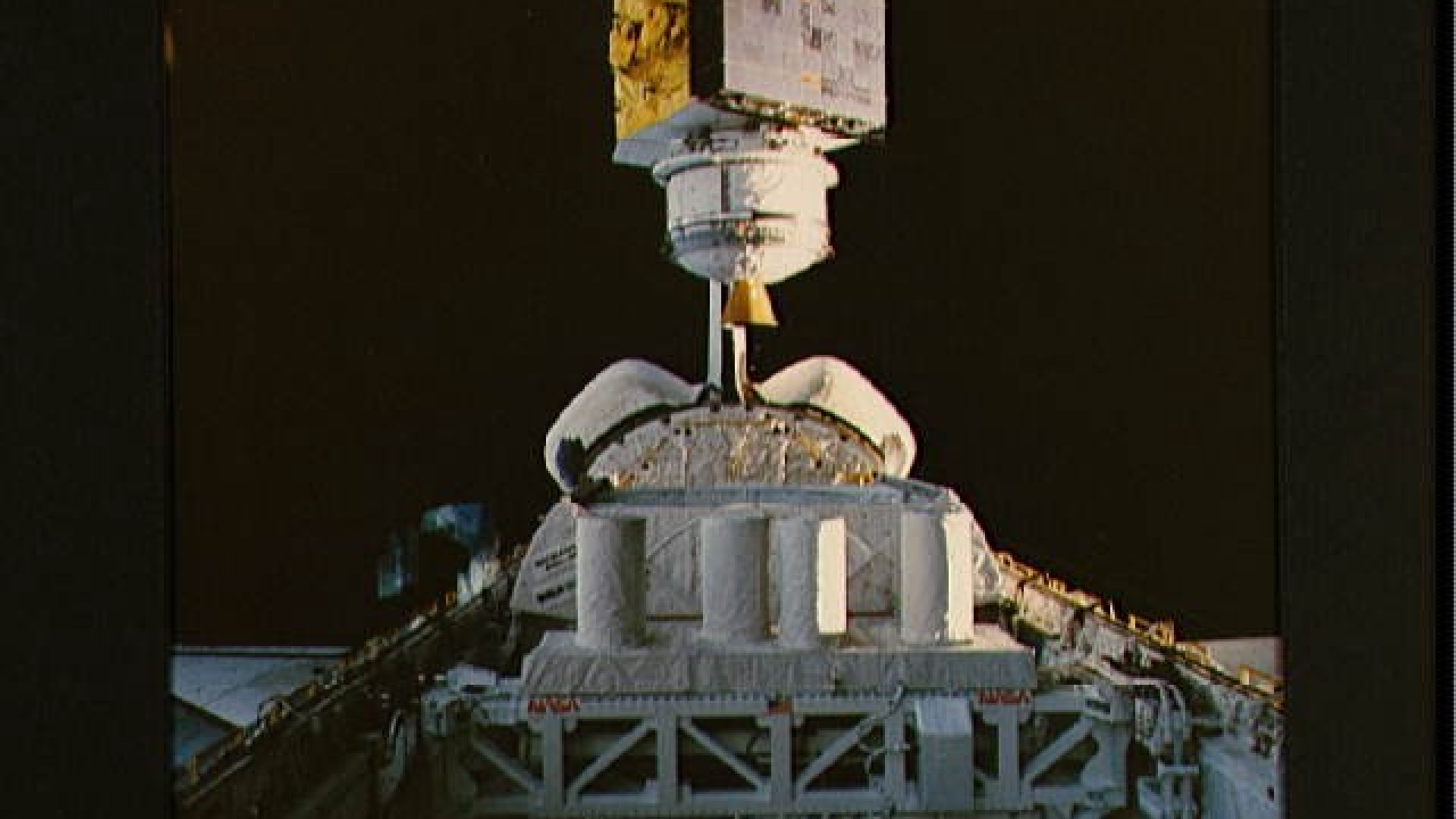

“We were in the simulator, on our way to space. The booster rockets had burned out and it was time for them to separate,” recalled Hoot. “A warning flashed for a ‘SEP-inhibit,’ which meant the boosters were not coming off like they were supposed to.

Quick as a flash, I reached over to the center console and grabbed the “automatic/manual” switch, flipped it into “manual”, hit the button, and shut down all three engines. In my rush, I had flipped the ‘external tank separate’ switch, not the “SRB-separate” switch and promptly separated the tank and booster rockets. We slipped into the ocean, where we all “died.” I “killed” my entire crew and never forgot about that. That’s when I established “Hoot’s Law.”

So when the two astronauts sat together in the simulator, with less than a year until the crew’s scheduled launch date, it was a perfect opportunity for Bolden to learn “Hoot’s Law.”

“On the day I learned about ‘Hoot’s Law, we had lifted off in the simulator and instantly lost one engine,” recalled Bolden.

“I quickly went to work, diagnosing the problem and determined that the engine failed because of an electrical problem. I told Hoot about my diagnosis and that I’d work the procedure to resolve it. He gave me the ‘ok’ and I flew through the procedure completely by myself. That was my first mistake. I identified the electrical system I believed was the source of the problem and shut it down before Hoot could say another word.

It quickly became very quiet. In my rush, I had shut down a good bus, not the bad one, and taken out a second engine. You can get to space if you lose an engine, even early in flight. You cannot get to space if you lost two engines early in flight. It took away our ability to abort and we slipped gently into the ocean. After that day, I always remembered ‘Hoot’s Law’.”

The similarities between Hoot and Bolden’s mistakes highlighted a critical lesson for the STS-61-C crew and many astronauts after — To err is simply human, so we should do everything in our power to take care of each other by working in pairs for critical evolutions such as failure analysis.

“Hoot’s Law” was just one of many examples of how the crew came to function as a team, with a single rule set in stone: “Anytime there is a malfunction, a minimum of two crew members must assess the situation and agree what is wrong before collaboratively making a decision.”

“The secret to solving problems is teamwork,” said Bolden. “You may think you’re good, but you’re probably not that good. ‘Hoot’s Law’ enabled us to achieve so much cohesion as a team.”

“All of us are only as good as humans and humans make mistakes. ‘Consensus’ is one of the most powerful ways to eliminate risk,” concluded Hoot.