By: Blake Scholl, Founder & CEO, Boom Supersonic

In North Carolina, bingo games are not permitted to last more than five hours. In Kentucky, public officers must take an oath stating that they have not participated in a duel. In Florida, unmarried women who go skydiving on Sundays could face jail time. While these comical laws do little real harm, one absurd regulation has had severe and lasting consequences: for over half a century, the US has had a speed limit in the sky.

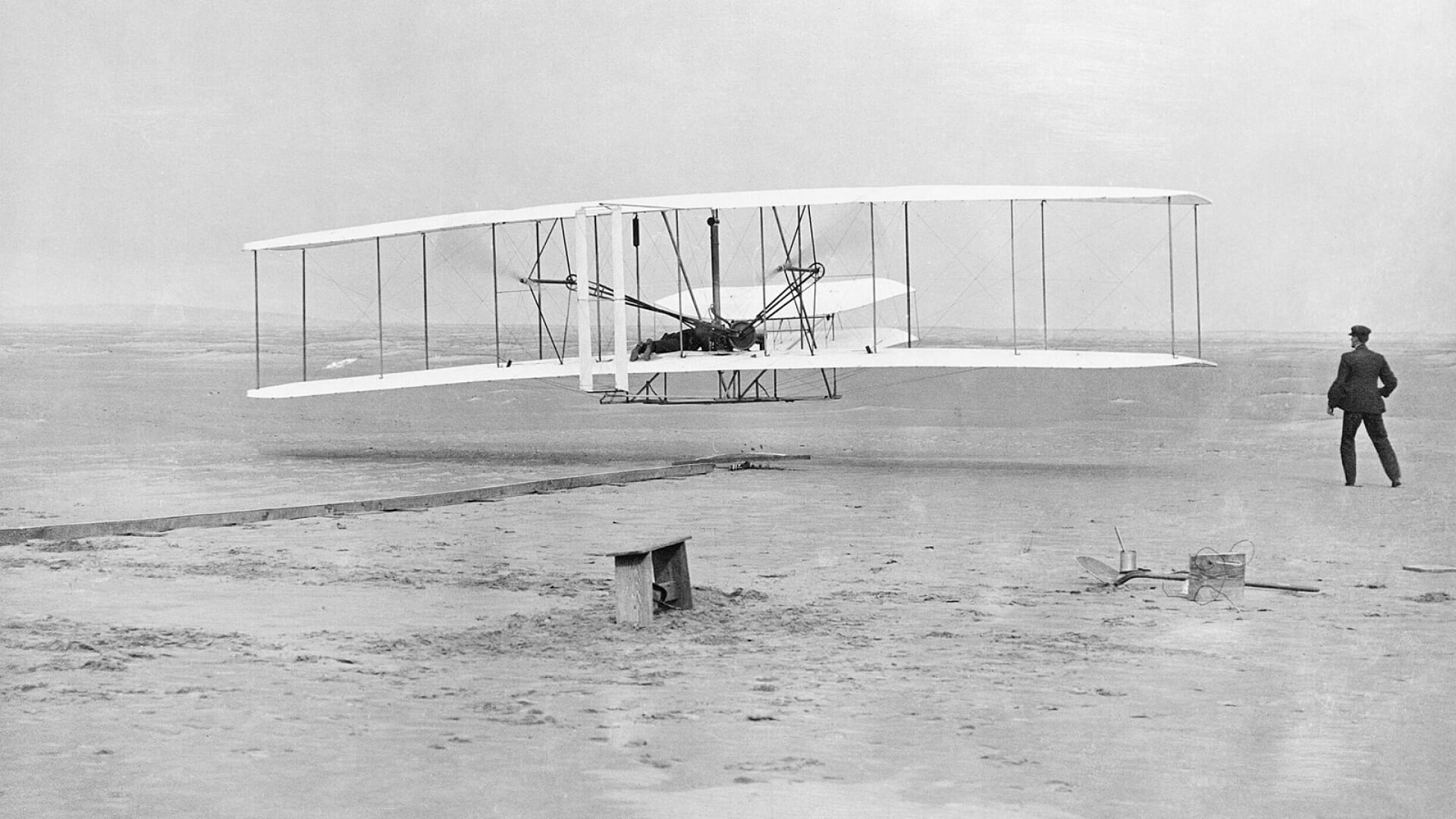

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. From the Wright brothers’ first flight in 1903 to the debut of the Boeing 707 in 1958, continual innovation in aviation brought ever-faster faster, farther-reaching flight. Increased mobility made the world a smaller place and enabled human connection across the planet—and created hundreds of thousands of jobs as the airplane became a top American export. Then, acceleration ground to a screeching halt.

On April 27, 1973 the Federal Aviation Administration enacted a ban on supersonic flight over the US.

Ostensibly, this regulation was about protecting the public from disruptive sonic booms. But what it actually did was ban speed—and with that it banned progress in flight. Not all supersonic flights make audible booms. And, like other sounds, sonic booms can be loud or quiet. A low-flying supersonic jet might rattle windows, while a high-flying one might make no noticeable boom.

The unintended consequence of this blanket ban was the stifling of American innovation in aviation. Supersonic passenger travel could have started with small supersonic aircraft, such as business jets designed for coast-to-coast travel. But the supersonic ban effectively made this product illegal in the US. Understandably, industry chose not to invest in supersonic aircraft, closing the door on what could have been the next step forward in flight. The world was left only with Concorde. While iconic, it was economically unviable, operating on few routes and at stratospheric fares attainable only to rockstars and royalty.

We also lost something deeper: the economic and cultural benefits of faster travel. Getting to your destination faster is not just a matter of time savings, it can be the difference between going and not going. Before the Jet Age, few went to Hawaii—and it was the speed of the jet that transformed Hawaii into the thriving destination it is today. In the absence of a new age of faster travel, innovation has been stifled, leaving us in what I believe is the dark age of commercial flight: we have gone more than six decades without a mainstream speedup in flight.

This speed limit has had a paralyzing downstream effect in aviation and for America. Left only to make small tweaks to existing products—Boeing’s latest jetliner bears a striking resemblance to its first—America’s top engineers increasingly joined computer and Internet companies where they were free to invent. This has left American leadership in flight vulnerable to competition from China—who is already producing clones of Western airliners—and recently announced a supersonic passenger plane. Unless we invent and build the next generation of aircraft in the US, leadership in aviation will pass from America to Asia, just like it has with chips. Let’s be clear: the supersonic race has started, and it’s critical that we win.

Advancements in materials science, aerodynamics, computers, and engine technology have made it possible to build supersonic aircraft that produce no audible sonic boom up to certain speeds—with a well-established physics concept called Mach cutoff, in which the sonic boom refracts in the atmosphere without reaching the ground. Additionally, public and privately funded research indicates that sonic booms can now be reduced to levels comparable to everyday urban noise, such as a car door slamming. Experts have argued for the establishment of a reasonable noise standard as opposed to an outright ban.

Implementing a noise-based approach for supersonic would align with the original intent—protecting the public from bad sounds while enabling a framework for innovation. Clearly, we should allow supersonic flight that does not create audible sonic booms. Then we can go further—a noise standard would allow even faster flights without objectionable noise. This would allow manufacturers to develop and test new supersonic aircraft, fostering a competitive market at a time when maintaining US leadership in next-generation aerospace technology is critical.

As the country looks to reindustrialize, we cannot hold back our own progress with a regulation that never should have existed. It’s time to say goodbye to the supersonic ban and embrace a better future of speed and innovation.

Blake Scholl is Founder/CEO at Boom Supersonic.