For speed, innovation and secrecy, no aircraft of its era came close to the SR-71 Blackbird. See it today at Seattle’s Museum of Flight.

What av geek doesn’t love speed, new technologies, advanced manufacturing methods, and the mysteries of a secret government program? Many aircraft embody these features, but none come close to the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird.

It purposely leaked fuel on the ground, had tires filled with nitrogen, and was made from one of the most expensive metals on earth. And, it’s still the world’s fastest plane.

Boom Supersonic explored the iconic Blackbird during a recent Museum Monday Twitter chat, with Senior Curator Matthew Burchette at Seattle’s Museum of Flight, where the Museum’s M-21 took center stage. It’s the first of the rare two-seat variants of the early A-12 (predecessor to the SR-71) and the only aircraft of its type remaining in the world. Burchette answered questions ranging from the SR-71’s paint job to its top speed.

Thanks to Burchette’s expertise, the chat covered a lot of ground — just like the Blackbird. Let’s dive into the key questions about this decades-before-its-time aircraft program.

First, quick facts.

Manufacturer: Lockheed Aircraft Corporation

Country of Origin: U.S.A.

Description: Twin-engine, two-seat, supersonic strategic reconnaissance aircraft

Materials: Titanium, titanium alloys and polymer composites

Engines: Pratt and Whitney J58 (JT11D-20B) turbojet engines

First Flight: December 22, 1964

Question 1: What was the mission of the SR-71 Blackbird?

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: The Blackbird was developed as a high-speed, high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft for the U.S. Air Force. It was outfitted with an advanced synthetic aperture radar system, an optical bar camera, and a technical objective camera wet film system to capture all sorts of information. A few missions included bomb damage assessment, strategic reconnaissance, and missions where time was of the essence. An SR-71 can be over a target much faster than a satellite.

Question 2: What’s the difference between the SR-71 and M-21?

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: The M-21 was like an A-12, but with a second cockpit added (like YF-12s) to house the Launch Control Officer for the D-21 drone. The SR-71 was also a two-place aircraft but was about 6 feet longer, was heavier, and carried enhanced reconnaissance equipment.

Question 3: Why was the SR-71 Blackbird painted black?

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: Prepare for a mind-blower. The Blackbird is not black but super dark blue.

Blackbirds earned their nickname because of their high-emissivity blue paint, which improved heat radiation, thus reducing thermal stresses on the airframe. In other words, the paint helped remove heat from the plane as it flew. The first A-12 initially flew unpainted but later were painted black on the periphery of the airframe where heating was greatest, like the leading and trailing edges, rudders, and the chines — the funky sloped surfaces at the edge of the fuselage.

Question 4: What about top speed? I have been told Mach 3.3 is only what it hit, but no one knows how much faster it could have flown.

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: There is a great story from Blackbird pilot Brian Shul who outran Libyan SAMs (surface-to-air missiles) during a BDA run (battle damage assessment) over Tripoli in 1986. He says that he was traveling a mile every 1.6 seconds, well above the Mach 3.2 limit with the throttles to the stops. However, if it’s faster than Mach 3.5, that remains a well-kept secret.

Question 5: How did the drone deploy?

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: The D-21 was carried on a pylon above the rear fuselage and between the vertical stabilizers of the M-21. Only four launches took place from an M-21: three from a parabolic arc, and one flying straight and level.

Just before launch, the Launch Control Officer (LCO) started the D-21s ramjet engine, and once the MD-21 combination reached Mach 3, the fuel tanks of the D-21 were topped off, the LCO triggered the explosive bolts holding the drone to the pylon, and it released.

Once the D-21 drone was released, the M-21 could go about its business. The launches using the arc to help separate the drone from the mothership were successful; the other was not.

Question 6: How did the SR-71 Blackbird engines work?

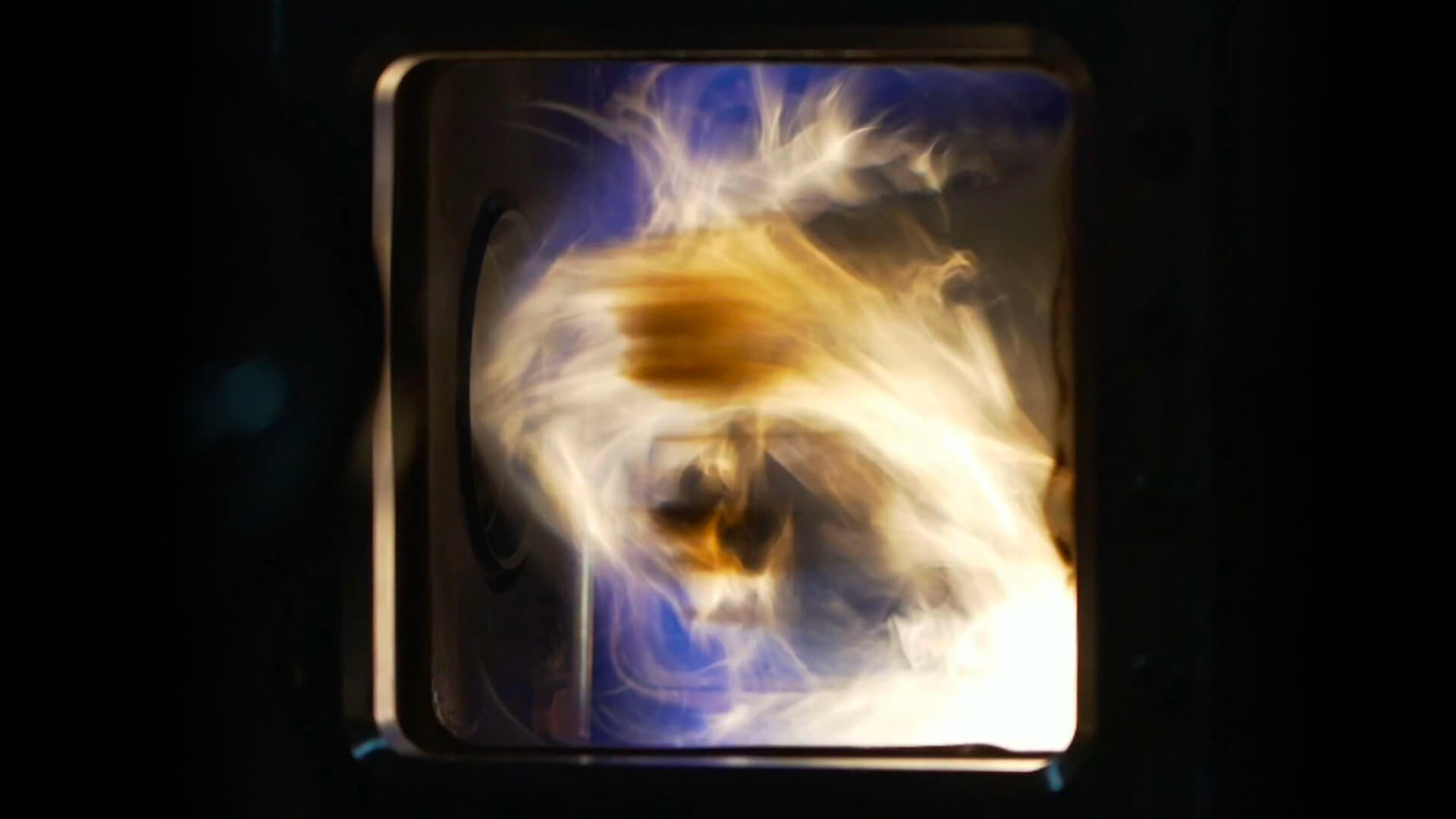

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: The J58 was an afterburning turbojet that incorporated a unique compressor bleed bypass at high Mach numbers. When opened, bypass valves bled air from the fourth compressor stage, and six ducts routed it around the compressor rear stages, combustor, and turbine.

The Blackbird’s power came from the combination of the inlet, engine, and exhaust functioning as a single unit. For example, cruising at leisurely Mach 3.2, only 18 percent of a J58s thrust came from the engine, while 58 percent of the thrust coming from the inlet.

In other words, at cruising speed, the engines functioned merely as flow-inducers, creating the low pressure that enticed air to enter the inlets. To oversimplify it, the aircraft sucked its way through the upper atmosphere! The bleed air re-entered the turbine exhaust at the front of the afterburner, where it increased thrust and cooling.

The whole process kicked in at Mach 1.6, and the percentage of bypass air increased up to Mach 2.8 when the bypass valves were fully open, and no air was going through the last six compressor stages at all. Because of its wide speed range, the J58 engine needed two modes of operation — one to take it from stationary on the ground and one to push it to nearly 2,000 mph at 70 to 80,000 feet.

In essence, it was a conventional afterburning turbojet for take-off and acceleration, but at 1.6, it used the compressor bleed to the afterburner for that extra kick! The way it worked at Mach 2.8 and above led it to be described as a “turboramjet.”

Question 7: Why did SR-71 Blackbird pilots wear a high-pressure (full pressure) suit?

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: Blackbird pilots used an S901 pressure suit that provided a livable pressure atmosphere for the pilot when the cockpit or outside is dangerous to the wearer. The human body does very well at ambient atmospheric pressures up to 10,000 ft. above MSL.

The suit provides both pressure and a pure oxygen environment to the pilot in their helmet. Under normal situations, the air and oxygen for the suit were furnished by the aircraft’s systems. But you had an emergency backup supply in your parachute backpack if you had to eject.

At sea level, barometric pressure is approximately 14.7 PSI, but at 85,000 ft., it’s just .25 PSI. So, you can see why you would need a special suit to survive!

Question 8: How many M-21s were there? Are there any others I can check out?

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: There were only two: 60–6940 and 60–6941. The latter was lost in a D-21 launch accident, while the former was used mostly for ferry flights. It is the only M-21 left, and the only place you can see it is — you guessed it — The Museum of Flight.

Question 9: What’s with the silver tires?!

Matthew Burchette — Museum of Flight: BF Goodrich developed a rubber compound infused with aluminum powder so the tires would not degrade during flight from the high heat they were subjected to.

They were also filled with 415 lbs./sq. inch of nitrogen instead of air. Since the aircraft’s fuselage could reach up to 900 °F at Mach 3.2, regular oxygen in its tires would boil and expand, causing them to rupture and burst like a bomb! Not only is nitrogen stable, but it’s also great at suppressing fires and is “non-hygroscopic,” meaning it does not absorb water vapor.

Fun fact, the front tires are NOT silver since they were located under the AC outlet for the cockpit. The front tires stayed cooler while the rear tires took the heat.

Many thanks to Seattle’s Museum of Flight and Senior Curator Matthew Burchette for sharing an insider’s look into the awe-inspiring SR-71. Conceived more than 56 years ago, it’s a testament to engineering and science.