Written by: Nick Sheryka, Chief Flight Test Engineer

What’s the next big thing in flight test? My bet is Starlink, the satellite constellation that provides broadband internet access worldwide.

Through our team’s preliminary tests on the XB-1 program, we’ve seen a preview of how Starlink could be a significant enabler of greater efficiencies in manned aircraft flight testing. We can see the possibility of a whole new world for flight test telemetry.

Here’s how the XB-1 team adapted a $500 Starlink Mini antenna to live stream from our Northrop T-38 chase aircraft, allowing our entire team to see each flight in real-time.

The flight test data challenge

As anyone who has tried to upload a massive file knows, moving data takes time. But when it becomes mission-critical to receive that data in real-time from an aircraft tens or even hundreds of miles away, designing the instantaneous link to the team on the ground (referred to as “telemetry”) is a challenge.

At Boom, our team is on a mission to integrate technology faster, using existing certified technology to create airliners that fly twice as fast and leveraging modern technology to perform previously arduous tasks in smarter and more efficient ways. The same applies to the XB-1 flight test program, which lays the foundation for Overture, our supersonic commercial airliner.

Telemetry is an aspect of flight test we identified as ripe for improvement—and—with the help of a Starlink Mini antenna, we surpassed even our own expectations. This isn’t the first time Starlink has been used to expand what’s possible, but it is almost certainly the first time anything close has been demonstrated using less than $1,000 in equipment in two weeks.

The chase plane use case

With the XB-1 flight test campaign nearly complete in 2024, the team had one nice-to-have, wish-list capability: live streaming video from our chase aircraft, a T-38.

Boom flies every test mission with another aircraft nearby to support XB-1. Whether providing an extra set of eyes to help manage airspace or quickly identify an oil leak, the value of having a second set of eyes airborne is well understood.

Well before the first flight, we discussed a potential live video feed into the control room and ruled it out as unnecessary to the mission. Yet, live eye-in-the-sky training can benefit members of the XB-1 team and aviation community who are not directly present during flight tests.

With this in mind, we decided to pursue a live video feed but would scrap the project if it risked compromising the mission’s safety.

Adapting a Starlink Mini antenna for a T-38

We elected to get our hands on a Starlink Mini antenna and see what was possible.

We worked with SpaceX to pair the Mini antenna with an aviation data plan, presumably removing software speed caps. However, the question remained: Would this modest antenna work at high speeds and changing attitudes? It would have to, or the idea would quickly disappear.

We had no intention of modifying the T-38 in a non-reversible way (no holes drilled, no wiring hacked into). While there are aviation-rated antennas available for Starlink, they were physically much larger and simply wouldn’t work with the T-38. The Mini was the only antenna that could fit into the T-38’s rear cockpit, allow for an occupant of that seat, and not impede the safe operation of the aircraft or the ejection seat.

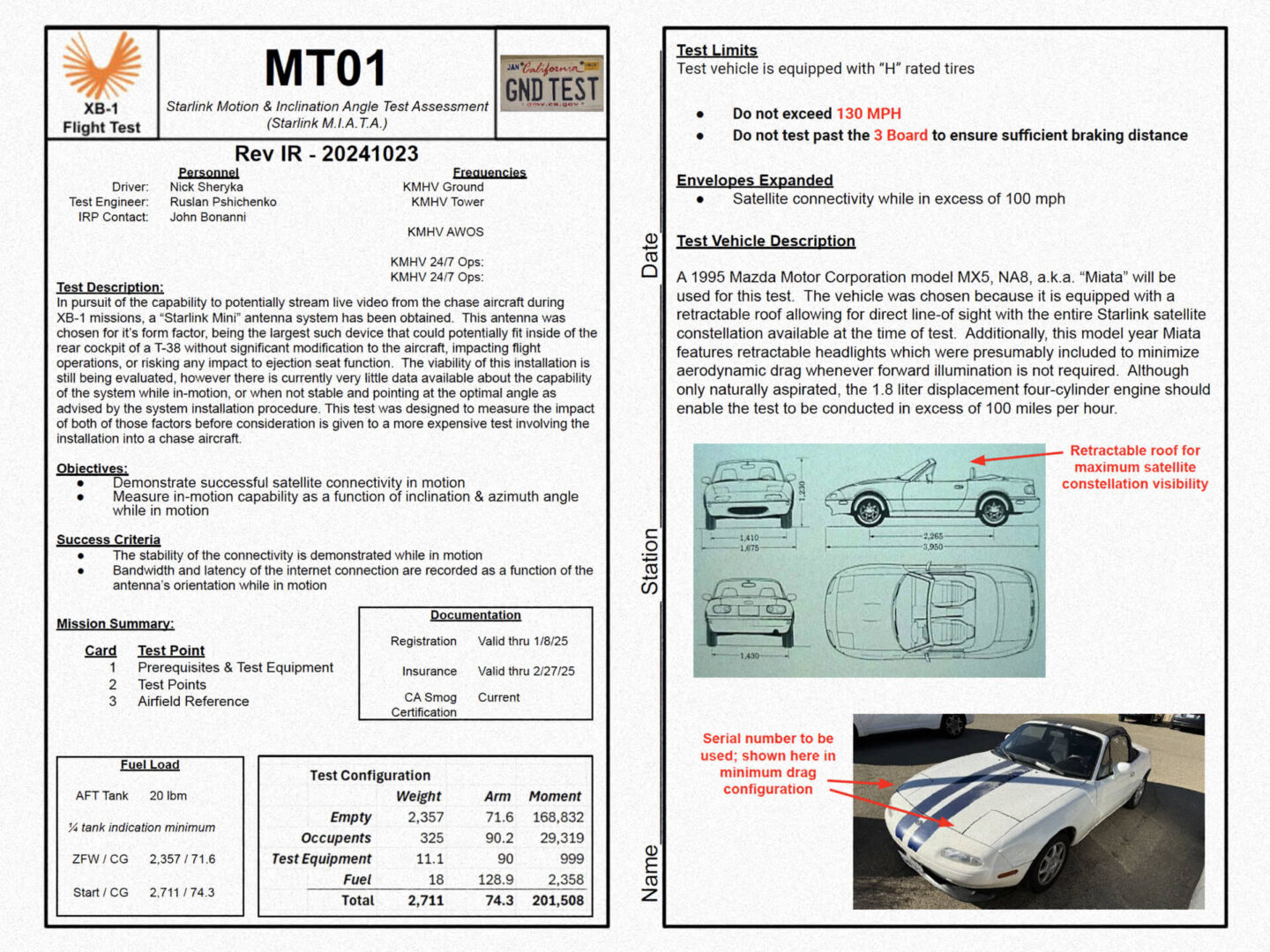

Testing on the ground: The Mazda Miata experiment

For our first test, we went very low-tech. You might say we went retro.

We aimed to ensure there were no basic configurations or setup gotchas that could be cheaply and quickly learned on the ground before investing in the cost of flying our T-38. We were also curious about the antenna performance sensitivity at different angles. While advertised as able to work “in motion,” we initially assumed that meant modest speeds as the system appeared to be targeted at a recreational market.

Starlink uses a phased-array antenna design, which is quite sophisticated. (For a deep dive into how they work, here is an excellent primer). No data was available on the system at anything above highway speeds, so our goal was to confirm the firmware did not have hard-coded limits that would disable the device—and that the diminutive phased-array device was up to the task.

We used a low-tech, low-cost test platform: my personal project car, a 1995 Mazda Miata, capable of greater than 100 mph (but not much more).

If I expected to perform this test legally driving the Miata, the nation’s highway system would not be a good choice. Instead, we obtained permission to test on the Mojave Air & Space Port’s two-mile-long runway in Mojave, California.

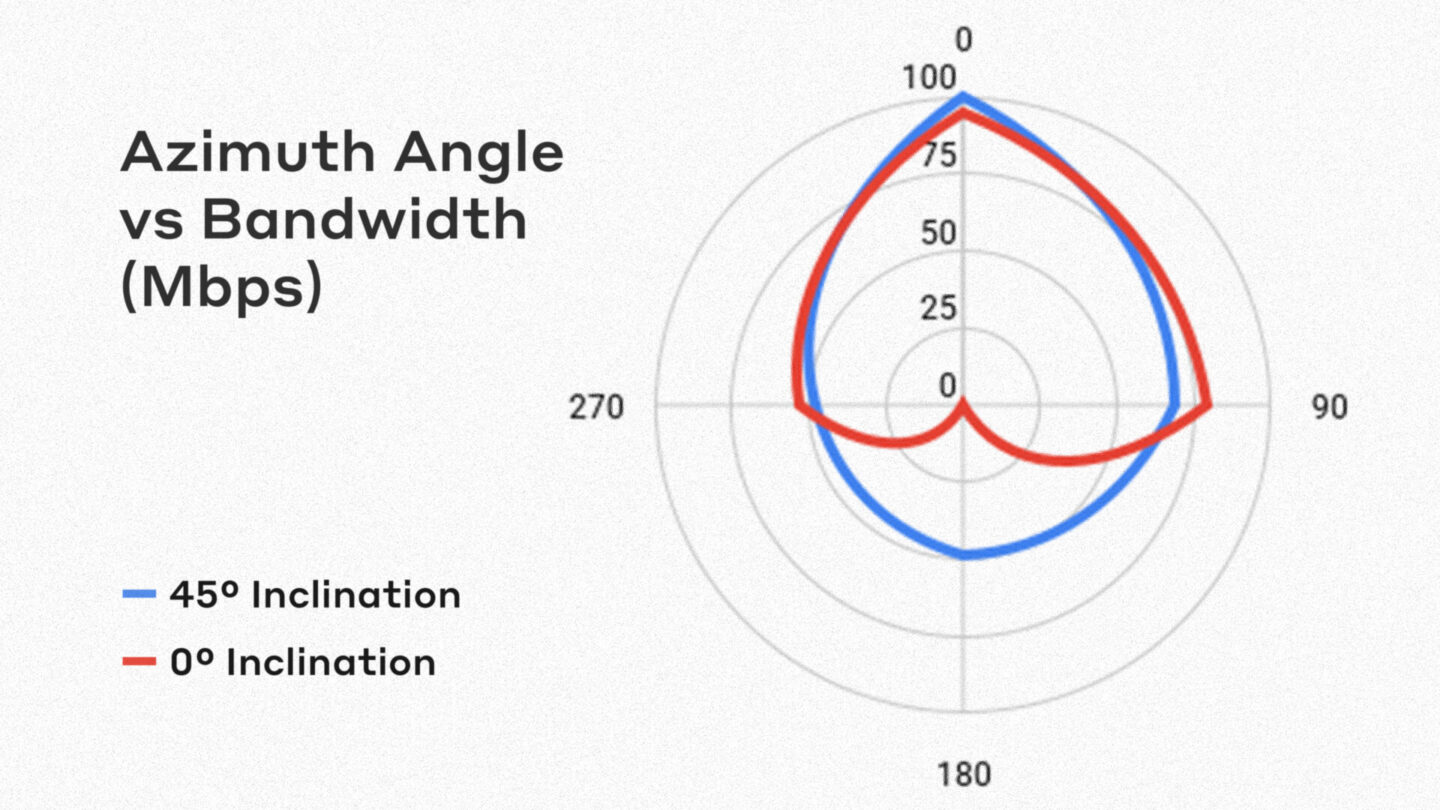

While the test cards below were primarily made in jest, we took the operation seriously and set clear safety limits and recovery actions. We varied inclination and azimuth angles while driving at greater than 100 mph down the runway, measuring download and upload speeds and latency. Each speed test took almost a minute to execute, so we had to make numerous runs… all in the name of science, of course. Some days are more fun at work than others.

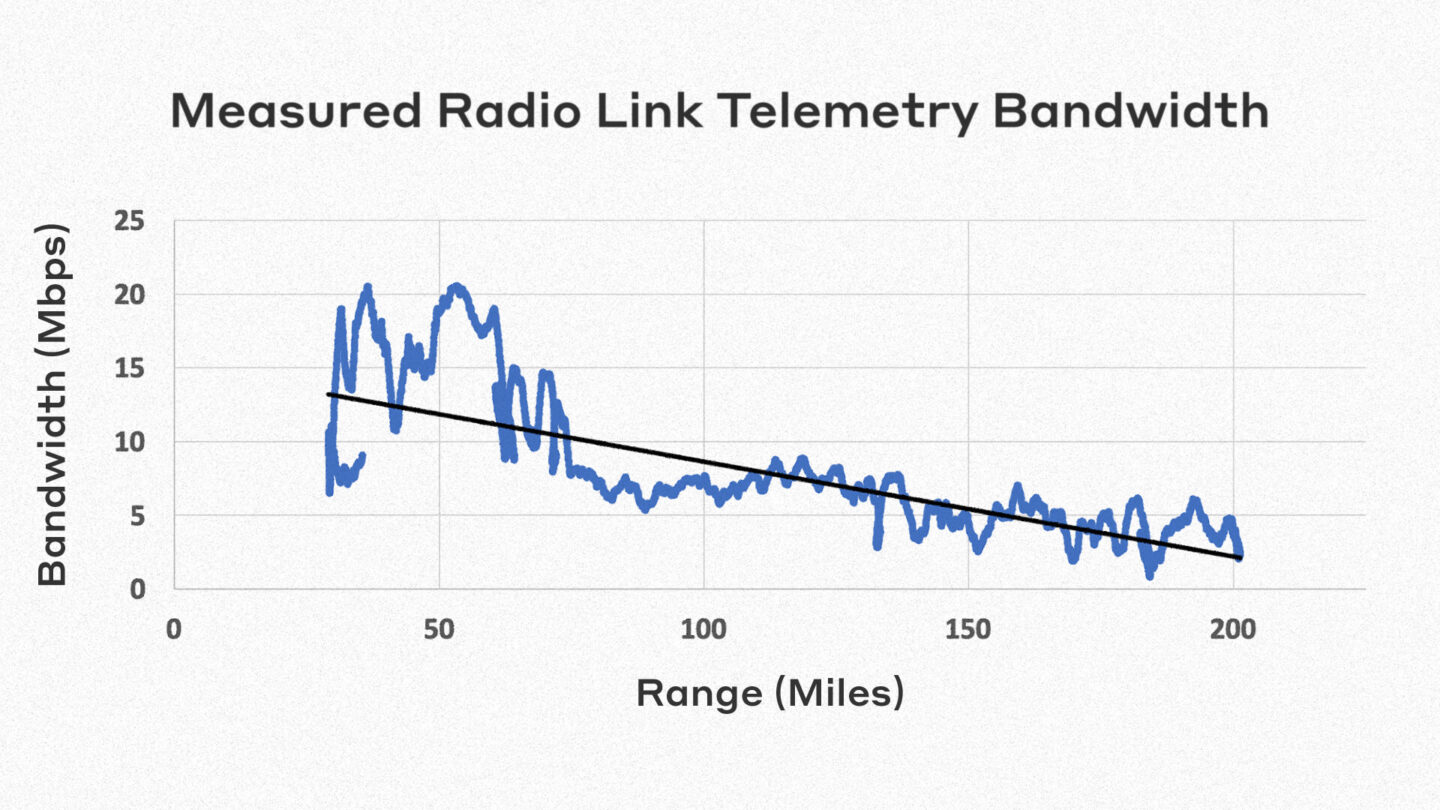

Surprisingly, the system performed well when pointed in any direction other than 90 degrees relative to the horizon (0° inclination). We consistently saw more than 10 mbps and, in many cases, significantly higher upload speeds. It was comparable to our speed with XB-1’s installed $150k telemetry system at ~100 miles. Starlink presumably has no distance (or altitude) constraint, weighs less than 10 lbs full up, and can easily fit into the cockpit of a Mazda Miata (or T-38). (Continue reading for a detailed description of XB-1’s telemetry system.)

From Miata to T-38

The Starlink Mini system worked at over 100 mph; how about more than 700 mph? Would it work in an airplane that is constantly changing its attitude all the time?

First, an effort was conducted to design a robust and flight-worthy installation for the mini antenna. With the aft cockpit chosen as the location, the design considered ease of installation and removal, upward visibility to the sky, and quick stow-ability. A hinged design that attaches with industrial suction cups to the transparency above the instrument panel was manufactured on a 3D printer.

Next, we mounted the Mini antenna, a battery, a circuit breaker, and basic battery health monitoring equipment within the custom 3D printed bracket (here is the design we used; feel free to download and build one yourself!) into the T-38. We flew it up to Mach 0.9+ while maneuvering. Again, performance stayed strong.

We then live-streamed from the T-38 for the final test during a simulated supersonic XB-1 mission, using a Mirage F1 as a stand-in. The ground team watched the uninterrupted real-time video of what the chase pilot saw at 34,000 feet and Mach 1.1 while chasing the target test aircraft.

Despite having built up to this test and understanding how the system works, that moment stands out. I was completely amazed by just how far technology has come. I was simply in awe of what we were doing at such a low barrier of entry—tremendous capability at orders of magnitude less cost and effort.

Telemetry, and why it matters

Before diving deeper into Boom’s telemetry system, here’s why connecting these vast amounts of data to the ground in real-time is crucial during flight testing.

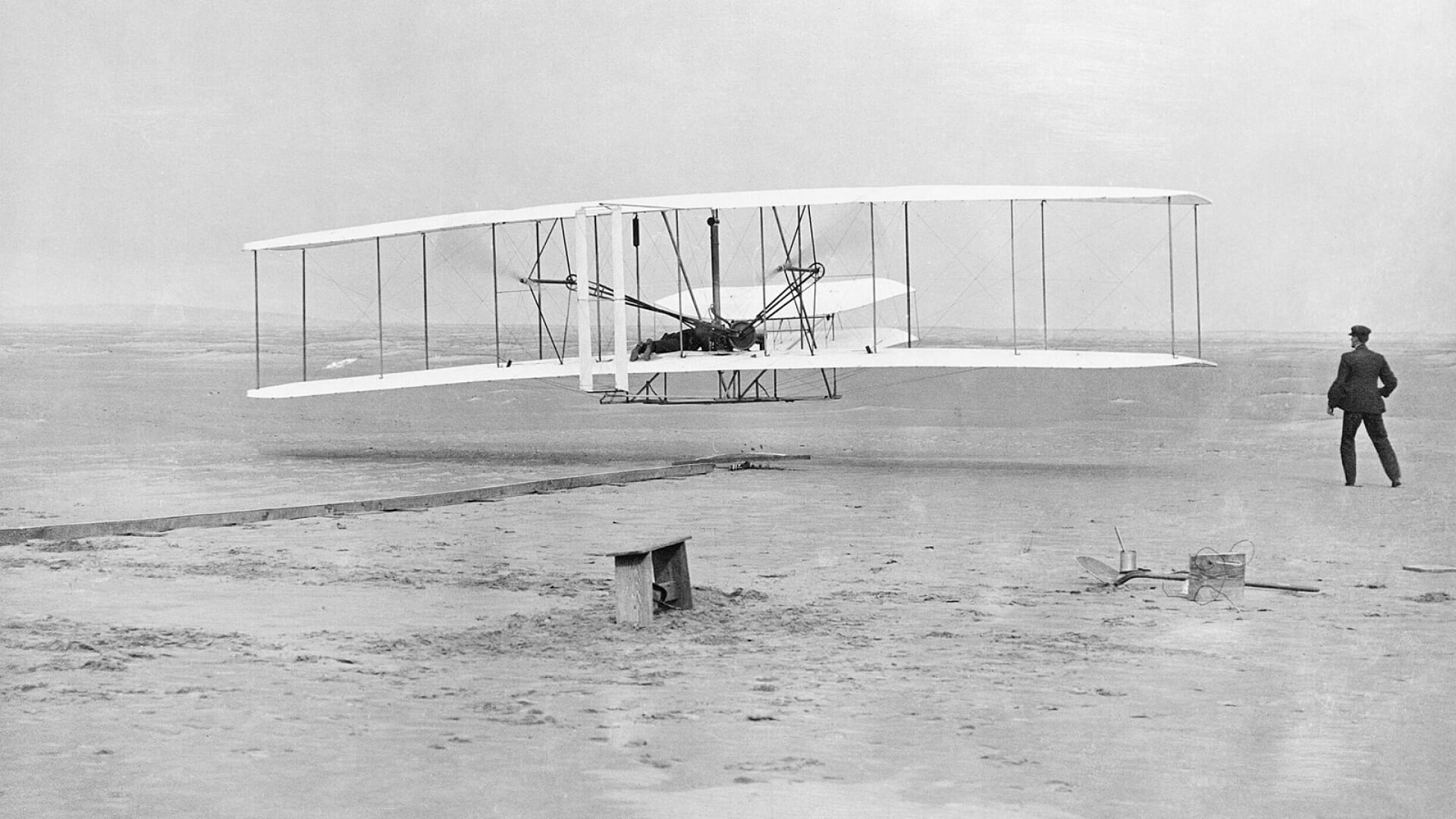

The Wright Brothers were the first flight test engineers (and test pilots). In December 1903, they flew without a pen and paper for note-taking. They relied on memory alone to track their actions and the aircraft’s response. Only one photograph exists to document this historic feat.

Since then, flight testing has advanced dramatically, generating enormous amounts of digital data used to prove performance and guide further testing.

Modern flight test campaigns produce massive amounts of data, most of which fall into two primary categories:

- Data Required (DR): These parameters must be recorded to avoid repeating tests. They can create hundreds of gigabytes or terabytes of data per hour, stored within onboard computer hard drives. Engineers analyze this data for hours or even days after completing the flight test mission, but there is no urgent need for the data in real-time.

- Safety Critical (SC): These parameters must be monitored in real-time to ensure tests can be conducted safely. For example, monitoring airspeed during a high-speed dive test ensures the aircraft does not exceed its safe limits.

A third, less formal data type is video, which provides high situational awareness for conditions that are difficult to capture through raw numeric data. Video can be hugely informative when paired with the recorded digital parameters. It can also provide otherwise missing context.

Live, real-time video is usually reserved for situations where quick assessment of dynamic situations, such as takeoff and landing, is helpful. It’s also used when video capability is the focus of the test.

Designing a telemetry system

When an aircraft has numerous Safety-Critical parameters, one pilot alone can’t monitor them all. Control rooms staffed with engineers allow for real-time oversight of these parameters. However, this demands a reliable, real-time data link between the aircraft and the ground.

After an aircraft program identifies the need for a real-time airborne telemetry system, the first significant design choice is whether to own the entire infrastructure end-to-end or to leverage an external network.

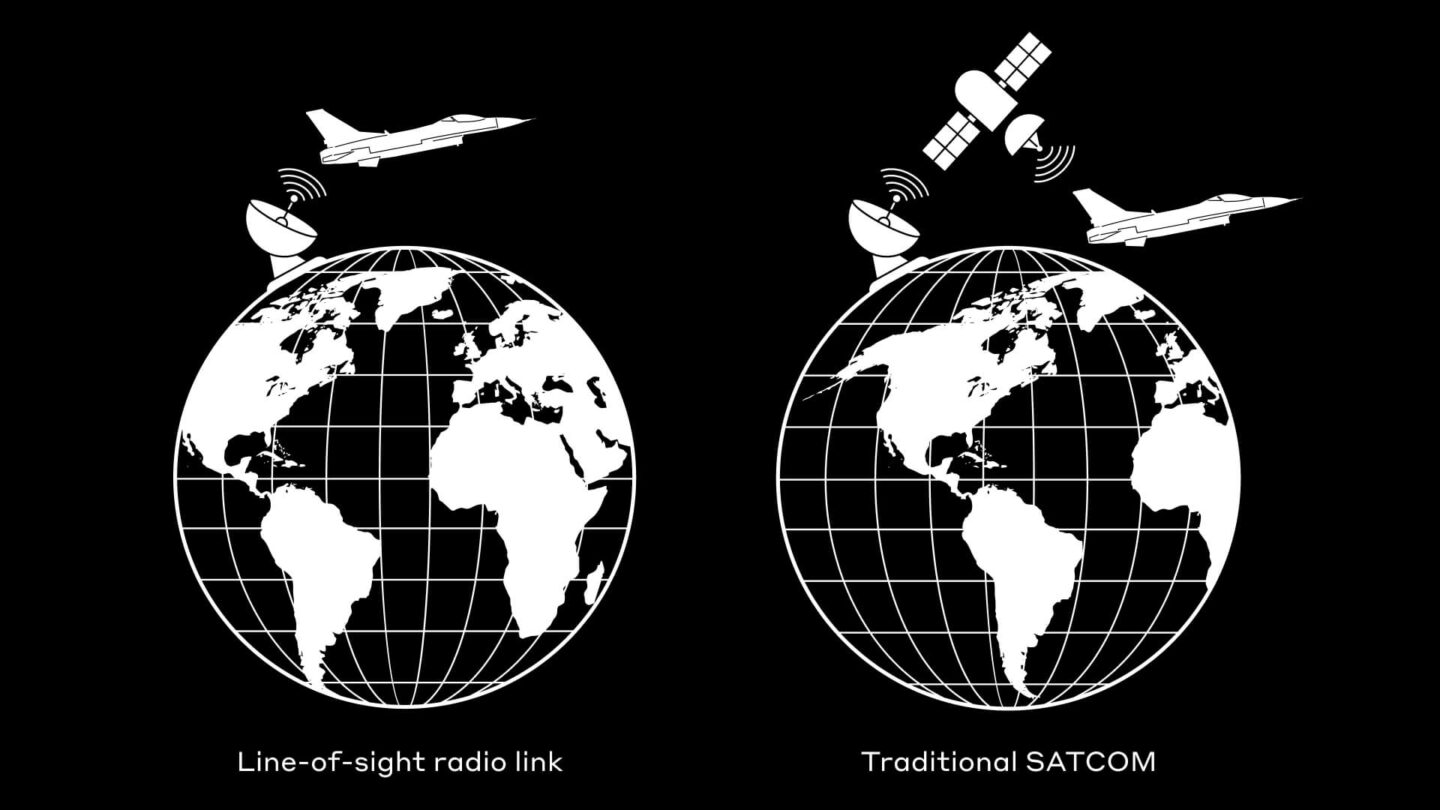

Commercial aerospace projects use proprietary line-of-sight radios or rely on cellular networks or satellite communication (Satcom) when operating far from home base.

- Cellular Networks: This is technically feasible but often limited by coverage gaps in remote flight test areas. Regulatory rules (analogous to being forced to put your phone in “airplane mode”) also complicate airborne use.

- Traditional Satcom: This is effective but tends to have high latency (due to geostationary satellites 22,000+ miles away), substantial up-front hardware, and recurring subscription costs.

Despite the drawbacks, many large aerospace companies use traditional Satcom and accept these high costs in return for reliable, long-range coverage. They may pair that system with a line-of-site radio link that can supplement the operation when close to the home base.

During XB-1’s early development in 2018, we identified the optimal telemetry system for our campaign. Given its 100- 200-mile maximum anticipated range, we used a line-of-site radio link system.

Telemetry for XB-1

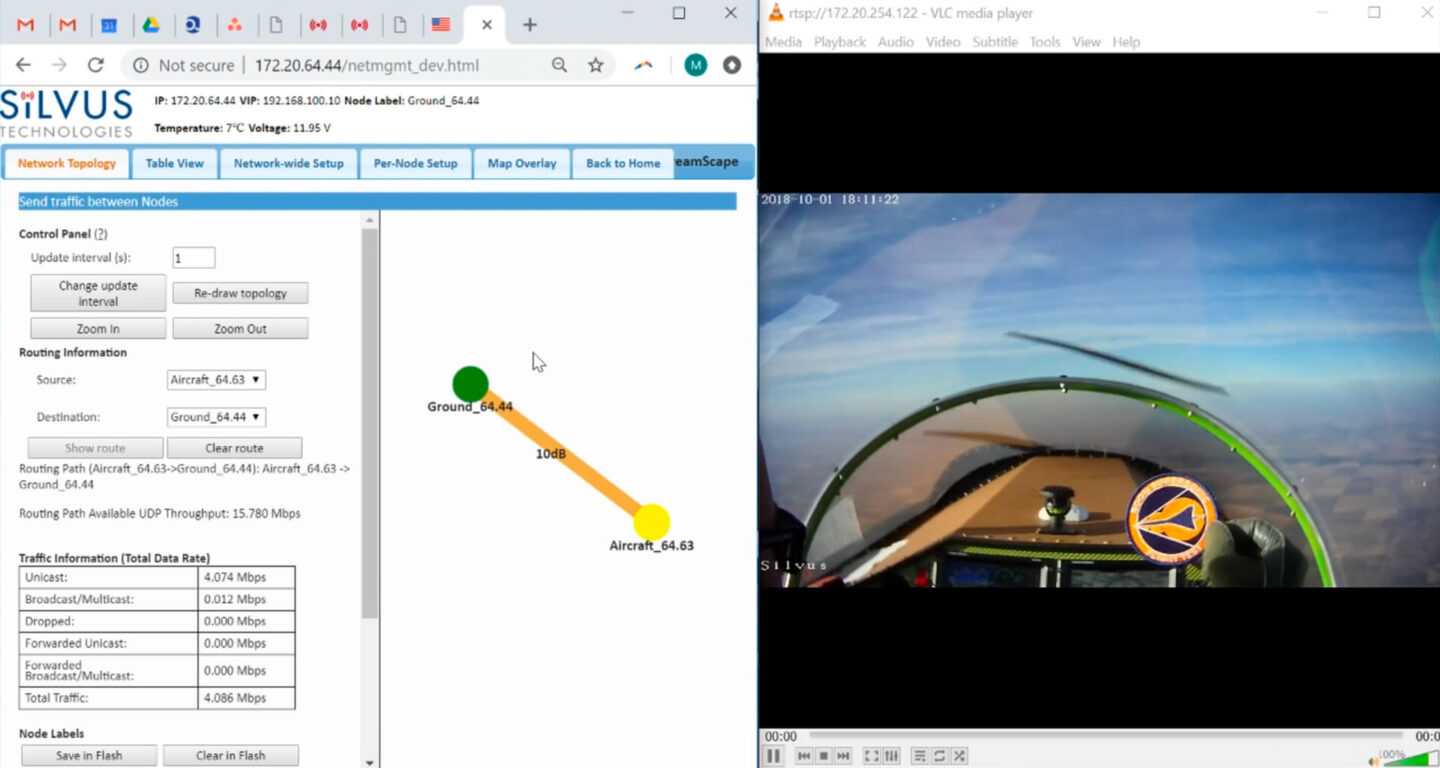

Boom developed a telemetry system with two S-band radios (Silvus Technologies) on board XB-1 and a complementary S-band radio mounted to a high-gain antenna at our ground station. XB-1 communicates over these radios on a private ethernet network, essentially making our control room an extension of its onboard avionics.

Early in XB-1’s build, we tested the system. We were highly impressed with the results for the cost and time invested. With the equipment mounted to my homebuilt experimental aircraft, we demonstrated 2-5 Mbps bandwidth at over 200 miles range and the ability to stream live high-definition video.

We further refined this telemetry system, which ultimately became what we use today for XB-1’s flight test program. The cost was close to $150K, and we used it whenever needed with no monthly service charge. This was our home-grown scrappy approach; similar commercially available plug-and-play options were available somewhere north of $1M.

A game-changer for XB-1 and all flight test programs

I once assumed SpaceX used custom hardware for its rocket launches, which enabled capabilities that were out of reach for aviation startups. Instead, the XB-1 team, a Mazda Miata, a $500 Starlink Mini antenna, and an on-demand data plan gave serious competition to legacy telemetry solutions.

SpaceX and Starlink have already demonstrated far more impressive feats than our test, such as live broadcasting from a re-entering Starship engulfed in plasma on the opposite side of the planet. Other Satcom systems have also supported aviation for decades. But the crucial difference is the small form factor: affordability and simplicity, now available off the shelf.

Starlink’s low-latency, lower-cost approach is poised to democratize real-time connectivity for flight test campaigns. Whether the application streams video from a chase plane or transmits safety-critical data to control rooms, this technology could open new possibilities and efficiencies in aircraft development and testing.

With further demonstration of its repeatable reliability for safety-critical flight test telemetry, Starlink might change the game for future flight test efforts and other small aerospace ventures worldwide.