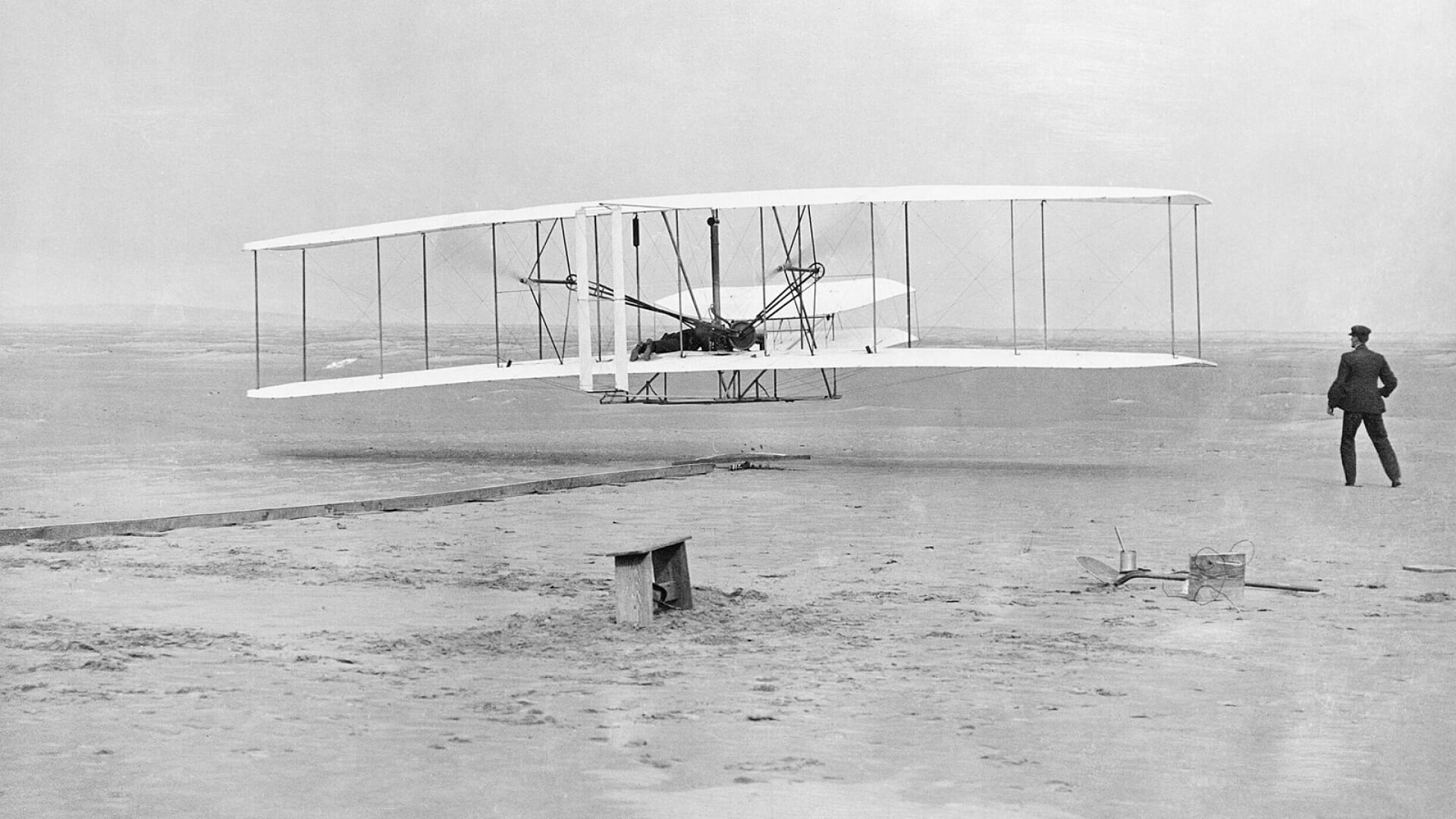

Rollout is a key milestone in an aircraft’s build, outmatched only by first flight. It’s a thrill to see the assembled aircraft for the first time, and also a pivotal time for the aircraft manufacturer. With the major milestone of rollout in the rearview mirror, the focus moves to ground and flight testing.

For many aviation enthusiasts, what happens after rollout is even more fascinating than the big unveil. While rollouts are a major step toward first flight, there are still milestones to meet before test pilots take the aircraft for a ride.

From extreme to extreme: the test vehicle journey

The particular aircraft you see at rollout serves many purposes, but it’s rarely destined to carry commercial passengers. Manufacturers don’t sell the first assembled aircraft to airlines. They’re mostly designated for testing. These aircraft endure thousands of tests that throw everything from ice chunks to bird carcasses at them. By the time they’ve endured full ground and flight testing, they aren’t suitable for sale.

In the case of Boom’s XB-1 supersonic demonstrator — the precursor to its Overture supersonic airliner — only two test pilots will have the opportunity to fly it during testing. Like many demonstrator aircraft, it is built to test principles and inform engineering processes. Those findings contribute directly to the design and build of Overture.

Ensuring safety, reliability and endurance

On the ground: Rollout marks the beginning of ground testing. Often a yearlong process, safety experts test almost every inch of the aircraft. They verify fuel tanks, systems, engines and more, ensuring that all systems meet requirements. Tests vary from aircraft to aircraft depending on the intended use. Commercial aircraft that could be in service for 30 to even 40 years undergo some of the most exhausting tests, ranging from flight loads simulation to ground vibration. While engineers are pushing the aircraft to its physical limits in the hangar, test pilots dedicate hundreds of hours to practicing in a flight simulator to prepare for the scenarios they might encounter.

Manufacturers including Airbus have a long history of building multiple test vehicles. Their A380 and A350 XWB each had a fleet of five test vehicles. In the case of the A350 XWB, the company implemented a 14-month test program that included a barrage of testing and more than 2,600 flight hours conducted on all five aircraft.

In the air: After rollout, commercial aircraft undergo a barrage of flight tests before flying civilian passengers. Weather tests are a fundamental milestone. These tests push aircraft to the hottest, coldest, dustiest and wettest extremes. Because weather is inherently unpredictable and no one can guarantee conditions, some tests are conducted indoors. Facilities such as the US Air Force’s McKinley Climatic Laboratory in Florida can replicate just about any weather conditions, except tornadoes and lightning strikes.

Following lab tests, pilots fly commercial vehicles to locations with consistently extreme weather. When it comes to biting cold, Iqaluit, Canada is a popular destination because it can guarantee some of the coldest conditions on earth. The Arctic town is the test site for many new aircraft, including Airbus’ 350–1000 test aircraft. The aircraft (and its crew) endured outside air temperatures between -18° and -26°F (-28° and -32°C), and as low as -35°F (-37°C) during overnight “cold soakings.”

The next stop is usually the desert heat of the Persian Gulf, then the hot and high altitudes of Ethiopia and Colombia. Test pilots often fly aircraft to La Paz in Bolivia to determine how well they can land and take off at high-altitude. It’s one of the highest international airports in the world at an altitude of 13,325 ft (4,061.5 m).

In the public eye: While the public might hear a lot about new aircraft, rollouts often happen in secret. Aircraft built for the military or government are usually kept quiet. People might not even know that a prototype exists. Take the iconic SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft. Its prototype, the YF-12, served as the basis of its design. But the build wasn’t publicly acknowledged until six months after first flight.

Built by Lockheed, the YF-12 flew at speeds of more than Mach 3 (three times the speed of sound) and at an altitude of 85,000 ft (25,908 m). Researchers used the YF-12 for experiments involving aerodynamic drag and skin friction, high-altitude turbulence, and more. The aircraft also advanced research on the health impacts for pilots flying at sustained high speeds.

Second lives in research and development

Flying Lab: Many prototypes and demonstrators go on to have second lives. Researchers use them for a wide range of testing, well beyond what the original designers imagined. Boeing’s prototype for the 737, the “Baby Boeing,” eventually became NASA’s Transport Systems Research Vehicle. NASA used it as a “flying laboratory” to test technological innovations, including a virtual cockpit and airborne wind shear detection systems.

The first 747 ever built — serial number 001 — never flew passengers either. Following rollout, it was a testbed for 747 systems improvements and engine developments for other Boeing airplanes, including the 777 engine program. Known as RA001, it completed close to 12,000 test flights before retirement to Boeing’s parking lot in 2003. (It wasn’t until 2012 that Seattle’s Museum of Flight greenlighted a two-year restoration project to restore it to its former glory. Today, you can view it at the museum.)

All eyes on first flight

Without a doubt, the most important event after rollout is an aircraft’s first flight. After months of ground testing, anticipation runs high for the awe-inspiring moment that an aircraft’s wheels lift off the runway for the first time. For XB-1, that milestone will take place in 2021. Like the X-1 — the test vehicle in which Chuck Yeager first demonstrated that supersonic flight was possible and safe for humans — XB-1 will also take its maiden flight in California over the Mojave Desert.