Conceived in the 1950s as a strategic nuclear bomber, the Valkyrie became a supersonic research aircraft in the 1960s

What aircraft began as a bomber but became a supersonic research vehicle? The North American XB-70 Valkyrie.

With its six engines, unique canards, variable geometry wing tips, and capacity to fly at Mach 3, the XB-70 was a sight to see. Today, only one remains in the world — and you can see it at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force (NMUSAF) in Dayton, Ohio.

Boom was honored to welcome NMUSAF Historian and Curator Dr. Doug Lantry for a recent Museum Monday Twitter chat about the XB-70. Joining us from the Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dr. Lantry shared his expertise on the aircraft’s history and legacy.

A truly groundbreaking aircraft, the XB-70 laid the foundation for future supersonic aircraft programs and provided invaluable insights into aircraft design for decades to come. It’s a personal favorite aircraft of many Boom employees, and an engineering marvel of its time. Here’s an up-close look at the XB-70 from the floor of the Museum with Dr. Lantry.

What was the original purpose of the XB-70 program?

The futuristic 500,000-pound XB-70A was originally conceived in the 1950s as a high-altitude, nuclear strike bomber that could fly at Mach 3 (three times the speed of sound). Any potential enemy would have been unable to defend against such a bomber. Cruising at 70,000 feet above the ground, developers believed it would be immune to interceptor aircrafts.

But by the early 1960s, new Surface-to-Air Missiles (SAMs) threatened the survivability of high-speed, high-altitude bombers. Less costly, nuclear-armed Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) were also entering service. As a result, in 1961, the XB-70 bomber program was canceled before any Valkyries were completed or flown.

But much was already invested. The U.S. Air Force still wanted to study high-speed flight, and NASA had a vested interest for its still-young SST (supersonic transport) program. After some back-and-forth on plans and funding, aircraft manufacturer North American built two test aircraft: XB-70A and XB-70B.

What was required to design the XB-70?

Talent and persistence. Designed without the type of “supercomputer” modeling that today’s engineers rely on, the XB-70 is the result of people thinking through high-speed aerodynamic problems, and then thinking through all the challenges of takeoff and landing. Dr. Lantry shares more.

Even though the aircraft looks like the latest, sleekest, modern airplane, in reality it’s two years older than the original Star Trek. It first flew in 1964. Captain Kirk was not in orbit until 1966.

How did the XB-70’s six engines work?

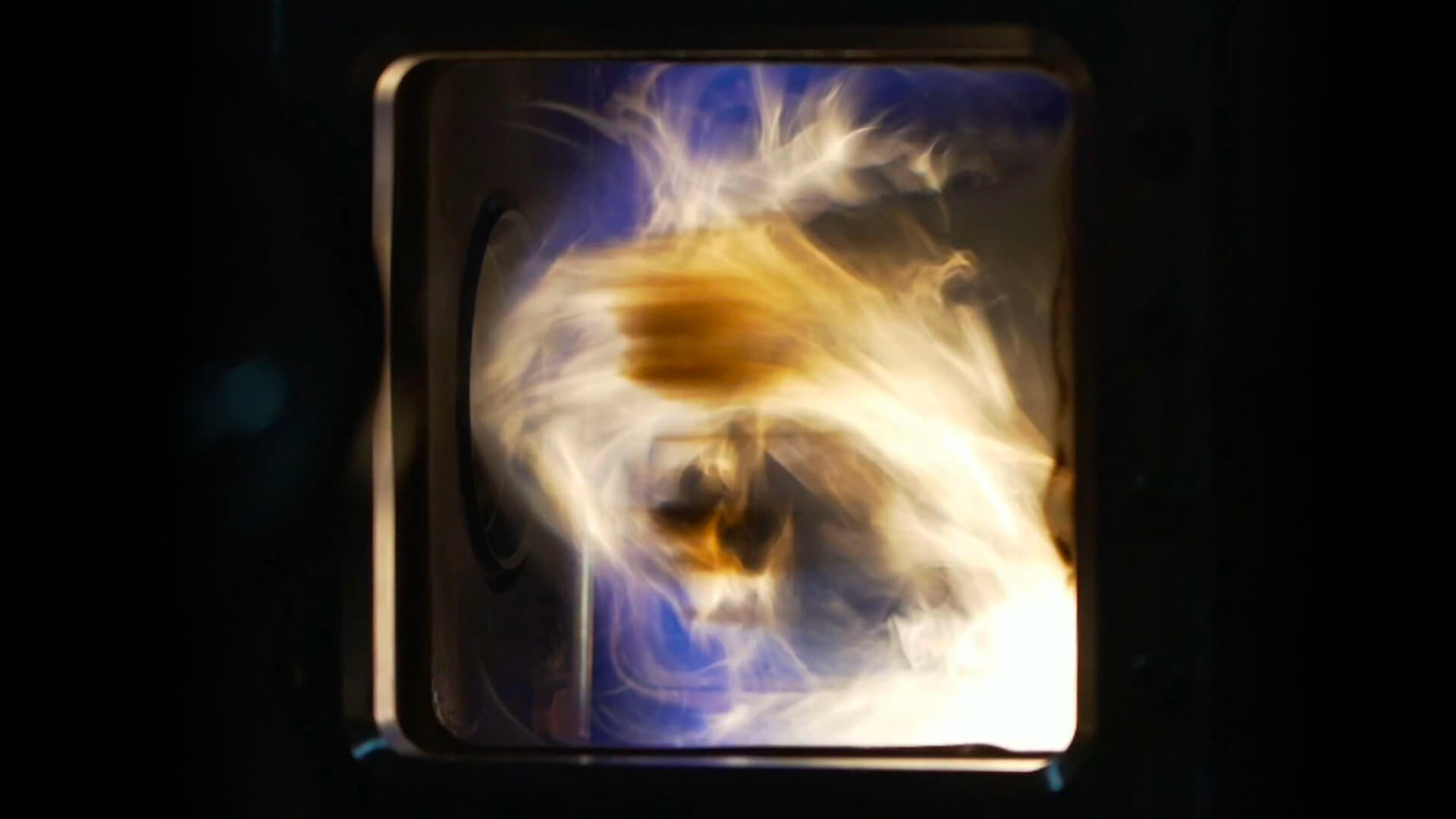

The XB-70’s six General Electric YJ-93-GE-3 engines are turbojets. Each developed up to 30,000 pounds of thrust, and were axial-flow engines, meaning the airflow was parallel to the rotating axis in the center of the engine. The engines compress air, mix it with fuel, and then ignite the high-pressure mixture to create thrust. Afterburners add still more thrust by adding more fuel to the hot exhaust gasses.

Confused? Let’s let Dr. Lantry walk us through this epic section of the aircraft.

Take a closer look at the “business end” of the XB-70:

How many XB-70s were built?

North American built just two XB-70s. The first XB-70 is on display at NMUSAF. The second was lost in an accident in June 1966 during a flight in which several aircraft were to be photographed in formation.

What can you tell us about the XB-70’s canards?

The XB-70 has unique geometry. What does that mean, exactly? Dr. Lantry explains this design feature.

Did the XB-70 ride its own shockwave, like a surfer on a wave?

In the XB-70, lift from pressure behind a supersonic shockwave — what engineers call “compression lift” — is an important feature. The forebody of the aircraft creates a shockwave, which in turn creates pressure at the front of the engine intake splitter and under the wing on the underside of the jet.

There’s no similar “counter” to the pressure behind the shockwave on the top of the jet. The result? Pressure under the jet is greater than above it, which translates into about a 30% increase in lift at supersonic speed.

Another key aspect of XB-70 aerodynamics is variable geometry wing tips. Take a look, and learn how they functioned at high and low speeds with Dr. Lantry.

What’s compression lift and how did it work?

Compression lift is a key component of XB-70 aerodynamics. Dr. Lantry explains.

Where can I see the XB-70?

The National Museum of the U.S. Air Force is the only place in the world where you can see an XB-70, because only one survives. It arrived at the Museum on February 4, 1969 and is currently on exhibit.

Did you know? The NMUSAF’s XB-70 never landed anywhere else but Edwards Air Force Base in California and Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. The other XB-70, which was destroyed, once visited Carswell Air Force Base in Texas for an air show in 1966.

As a curator, how do you approach sharing the XB-70’s story?

Dr. Lantry closed the chat with observations about the art and craft of sharing the history and heritage of the XB-70 with new generations of aircraft enthusiasts.

Thank you to Dr. Doug Lantry and the team at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force for going behind-the-scenes with the XB-70 Valkyrie.

Curious to know more?

Plan an in-person visit to the Museum and see more than 350 aerospace vehicles on display and walk through multiple historic aircraft, as well as four Presidential Aircraft. You can also take a virtual 360 tour of the Museum’s exhibits.