It’s 6 a.m. at the Mojave Air & Space Port in Mojave, California. The entire Boom Supersonic XB-1 team is gathered in a conference room with Chief Test Pilot Tristan “Geppetto” Brandenburg. He’s there to brief them on XB-1’s eleventh flight, slated to take off in about an hour.

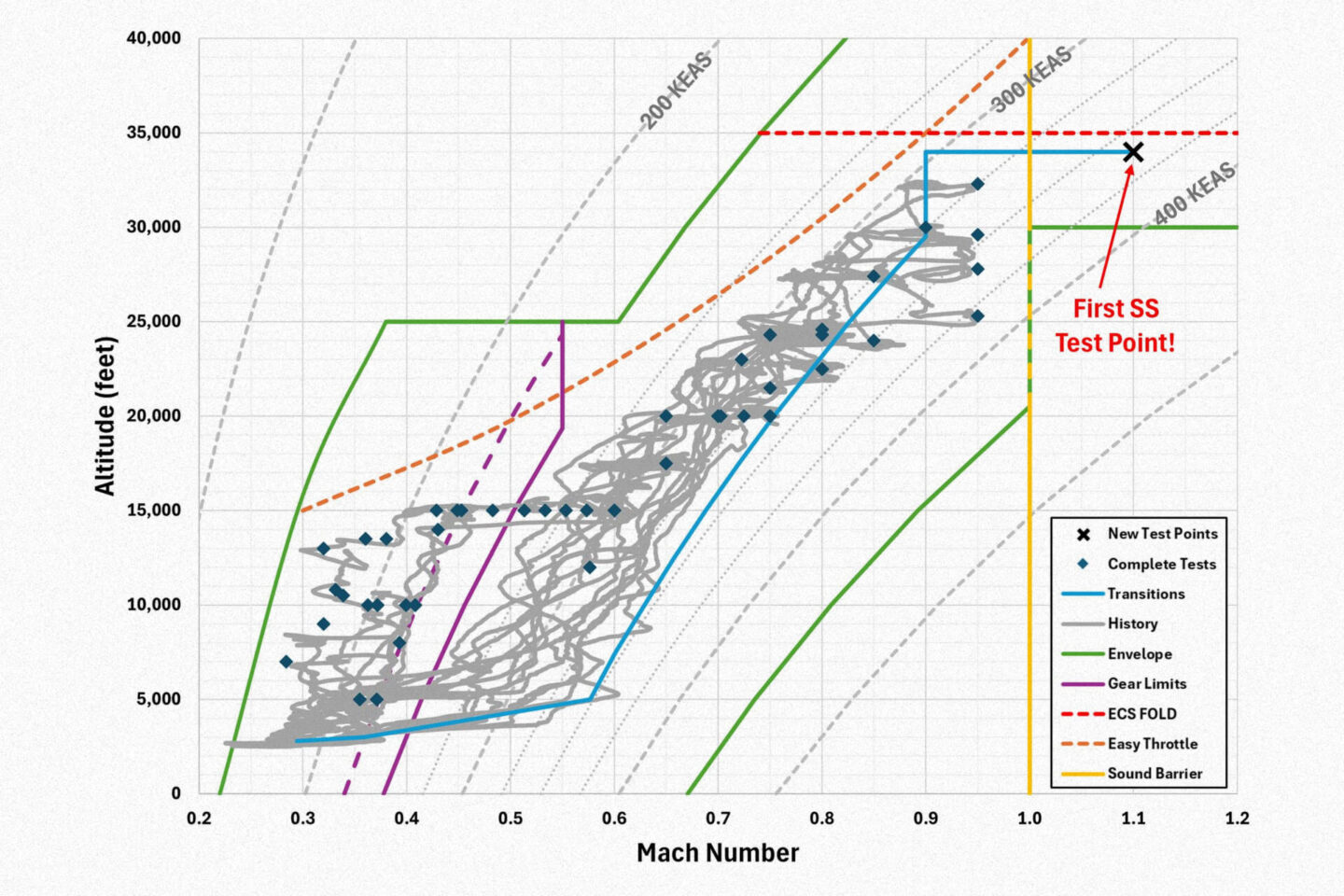

Geppetto walks the team through the flight test cards, which outline each aspect of the flight. Today’s flight focuses on dynamic pressure. It’s one of the final tests before breaking the sound barrier and reaching Mach 1.1. On today’s flight, the team must see a higher dynamic pressure at a subsonic Mach number, as well as Mach 0.95. These results allow the team to make predictions for supersonic flight and continue the flight test program safely.

Following the test cards, Geppetto reminds the team of key safety considerations and walks them through the potential challenges of the flight.

Then he pauses. His next comment is unexpected yet well-received: “Take a moment today to appreciate how amazing this aircraft is—and how amazing what we’re doing is,” he advises. “It goes by so quickly, and I have to remind myself to stop and take it all in.”

Geppetto wraps up the meeting with additional instructions and heads to the hangar. He’ll be airborne soon.

Preparing for supersonic flight

XB-1’s pre-flight briefings reflect days, weeks, and even months of testing and preparation. But there’s much more to it, especially when it comes to supersonic speed.

So, we caught up with Geppetto to ask how XB-1’s supersonic flight will be different, what people can expect on the ground, and how he prepares for each flight. Here’s our Q&A:

What is the flight path for XB-1’s supersonic flight?

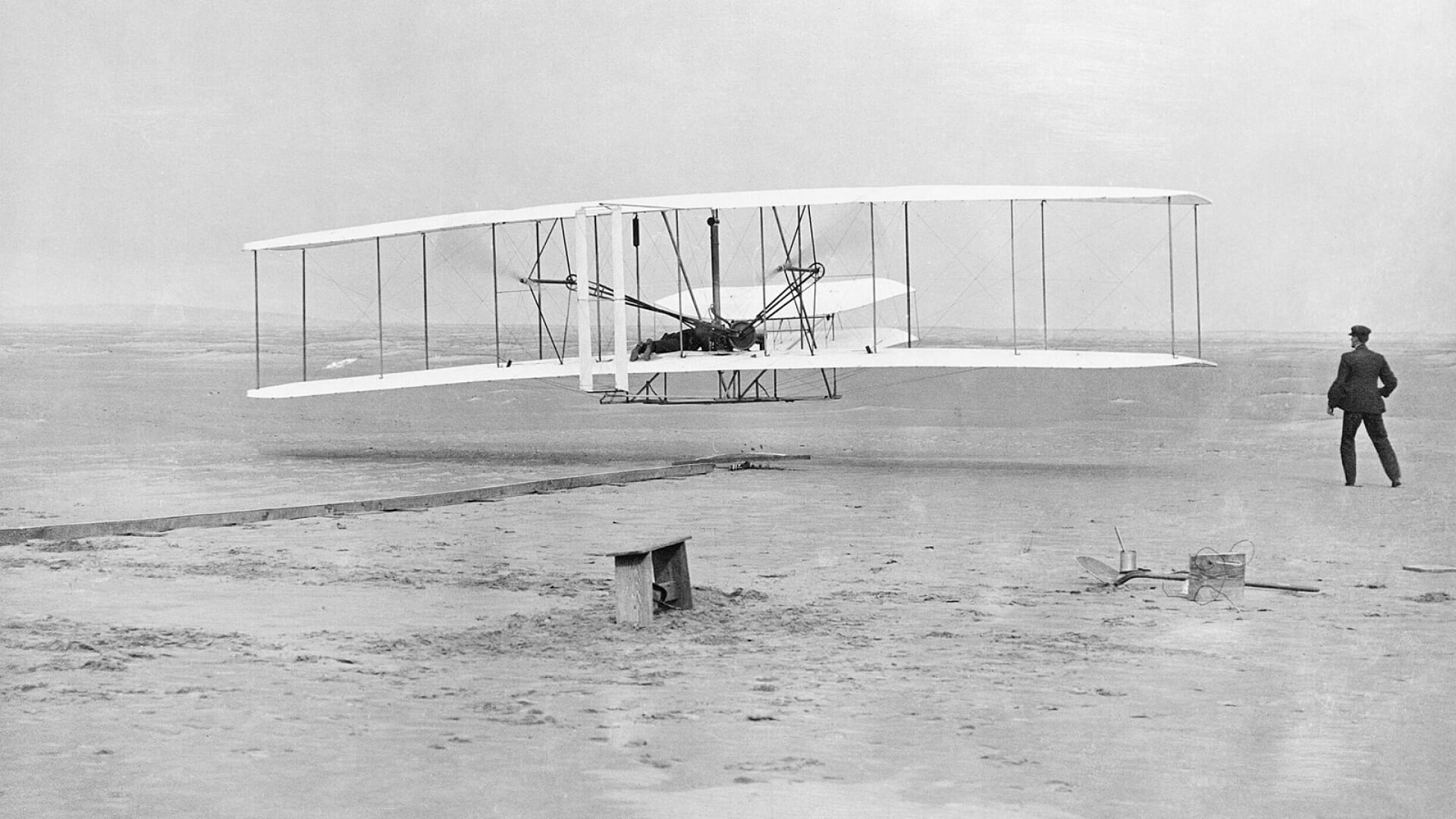

Boom has been authorized to fly in two specific airspaces: the Bell X-1 Supersonic Corridor and the Black Mountain Supersonic Corridor near Edwards Air Force Base in Mojave, California. In 1947, Chuck Yeager became the first person to exceed the speed of sound in this airspace. His aircraft? The Bell X-1.

XB-1’s supersonic flight will be between 30 and 45 minutes. Each supersonic run is expected to last close to 4 minutes.

How will you determine the exact speed of XB-1’s supersonic flight?

Our first supersonic flight will be Mach 1.1. There is quite a bit of uncertainty in the transonic regime between 0.95 and 1.1 as local airflow over different parts of the aircraft transitions from subsonic to supersonic, and back to subsonic, at different times. (It causes shockwaves to interact, which sharply increases drag and can shift the pressures and loads on the aircraft around in ways that are difficult to model and accurately predict.) This region of the envelope is challenging to model accurately, and we want to be very careful at these speeds.

Will people on the ground hear XB-1’s first sonic boom?

XB-1’s first sonic boom at Mach 1.1 probably won’t reach the ground. We plan to fly at 34,000 ft., so the energy will likely dissipate over the roughly six vertical miles between the aircraft and the ground.

How often do you practice in XB-1’s simulator?

Before each flight, I practice several times in the XB-1 simulator. It’s a very useful tool to practice airspace and fuel management. It also gives me our best prediction of how we expect the aircraft to behave in each new condition.

In addition to the test points, I always practice several emergency scenarios, such as engine failures at very inconvenient times and landings with the Inertial Navigation System (INS) and Stability Augmentation System (SAS) failing. Finally, we run the profile at least twice with the entire control room: once with the flight going as expected and once with some sort of failure or emergency.

How does it feel to accelerate into supersonic speed?

A common misconception is that the pilot feels extreme G-forces at supersonic speeds. This is not true.

Once the aircraft is steady at a given airspeed and not in a turn (unaccelerated), I only feel the force of gravity (1 g). Acceleration in the x-axis (the direction of thrust) is noticeable but far less than even 1 g. A jet on a catapult shot from an aircraft carrier subjects the pilot to far more acceleration (g force) in the x-axis than I feel in XB-1, even at maximum thrust.

How does it feel to accelerate from subsonic to supersonic?

The actual acceleration from subsonic to supersonic is fairly gradual. There is a phenomenon known as the transonic drag rise in which the drag on the aircraft increases sharply at a certain Mach number. Every aircraft has a drag divergence Mach number. For aircraft not designed for high subsonic flight, this can be as low as Mach 0.8.

XB-1’s drag divergence Mach number is around Mach 0.95. Drag continues to rise and then peaks around Mach 1.0. On XB-1, drag begins to decrease at around Mach 1.1. This transonic drag rise is part of the reason for the term “sound barrier.” High-speed aircraft pilots during and shortly after World War II reported several phenomena approaching the speed of sound, including increased drag, which gave the impression that a physical barrier prevented an aircraft from exceeding the speed of sound.

Some aircraft are capable of supersonic flight but have difficulty accelerating in level flight through the transonic drag rise. To achieve supersonic speeds, these aircraft can trade potential energy for kinetic energy by diving from a high altitude through the transonic drag rise and then achieve level supersonic flight at a lower altitude. Other aircraft not designed for supersonic flight may be able to achieve supersonic flight in a dive momentarily but cannot sustain it. XB-1 is designed to accelerate through the transonic drag rise and sustain level, supersonic flight.

What do you expect during XB-1’s acceleration to Mach 1.1?

- Pitot-static instability or inaccuracy

- Pitch trim changes and sensitivity

- Pitch sensitivity

Here’s some background information.

#1 Pitot-static instability or inaccuracy during the shock wave.

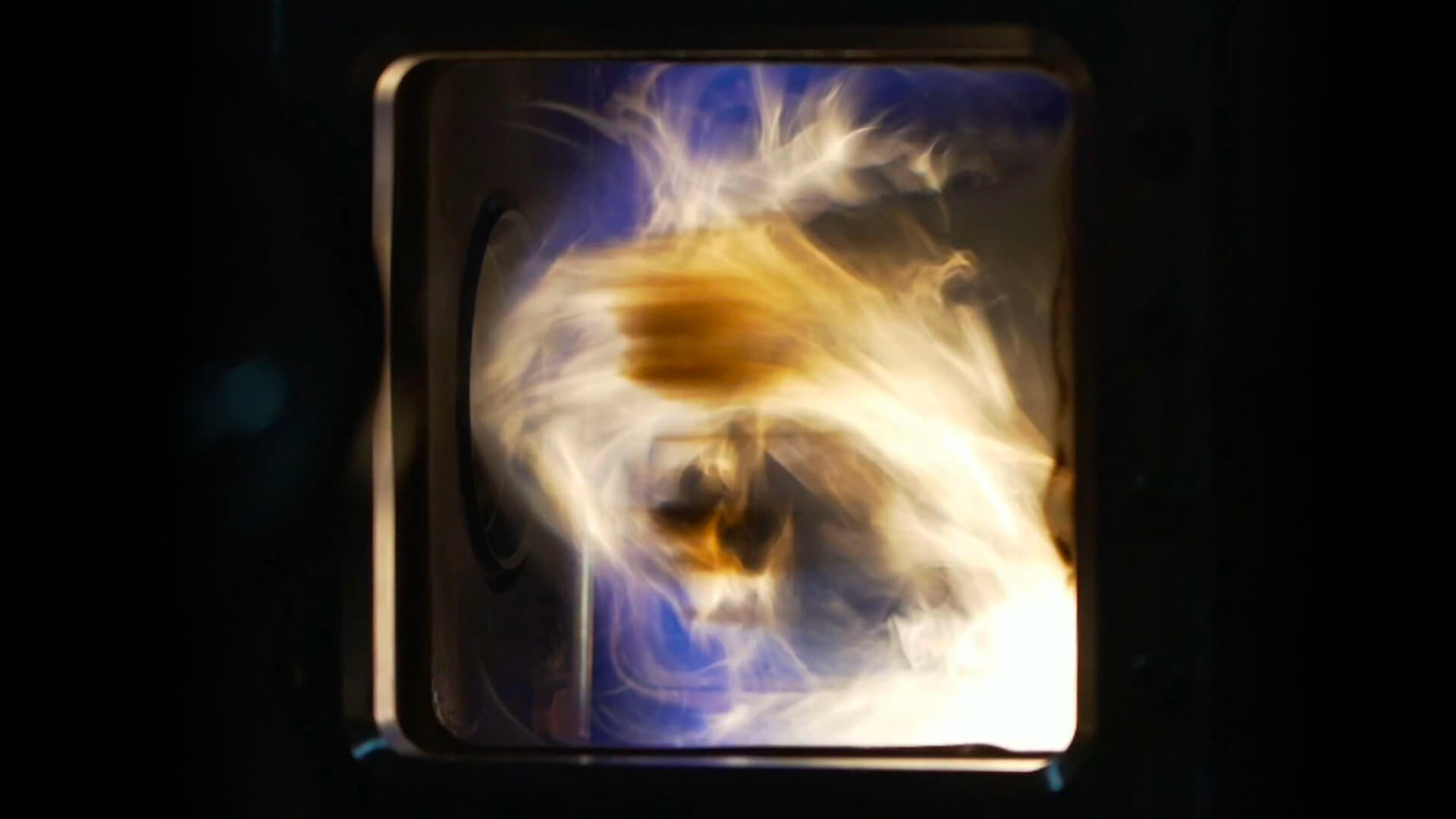

A shock wave is a near-instantaneous density, temperature, and pressure change over an extremely small distance.

Airspeed and altitude are calculated using pressure measurements. The Pitot tube (named for its inventor, Henri Pitot) measures total air pressure and static air pressure. The difference between total and static pressure is the impact pressure from which velocity is calculated.

As the shock wave passes over the static pressure ports, I may see a sudden jump in airspeed and altitude. This “jump” also occurs in the T-38 and F-5. It confirms that I am supersonic in those aircraft.

XB-1 has two separate Pitot-static systems, the primary system being the long, skinny nose boom, which has a Pitot tube at the very front. This is intended to minimize error, but a slight change will likely occur as the shock wave passes over the static ports. The secondary system is closer to the cockpit. So far, we have seen a good correlation between altitude and airspeed on both systems, but the secondary system may be slightly inaccurate while supersonic.

2 Pitch trim changes and sensitivity

While XB-1 is still subsonic, airflow over parts of the aircraft—most notably the wings—is supersonic. As airflow over the wings and the elevator (pitch control surface) accelerates, a shockwave forms where the airflow transitions from supersonic to subsonic. As it accelerates closer to Mach 1, the shock wave moves aft on the surfaces. As the shockwave moves, the center of pressure moves as well.

Typically, while subsonic, the center of pressure is around the quarter chord or 25% down the length of the wing. While supersonic, the center of pressure is around the half chord or in the middle of the wing. This shift in the center of pressure causes a nose-down pitching moment.

Generally—almost universally—as an aircraft accelerates, the pilot must trim the nose down to maintain level flight. However, while accelerating through transonic, I expect to need to trim the nose up. This is modeled in the simulator and something I have practiced to the point that I barely notice it anymore.

3 Pitch sensitivity

In preparation for flying XB-1, I flew the F-104 with Starfighters International in Florida. Our models indicated that XB-1 would handle most similarly to the F-104 with the SAS off.

One of the key takeaways from that flight was that pitch control became extremely sensitive during the transonic acceleration. As airspeed increases, small changes in the angle of the elevator result in increasingly higher pitch moments and, therefore, pitch rates. Couple this high effectiveness with the shift in the center of pressure, and it’s not hard to imagine it can make the aircraft sensitive and possibly even somewhat unpredictable.

What does it mean to expand the flight envelope?

XB-1’s early flights focused on basic handling qualities (how the aircraft responds to pilot inputs) and system checkouts, such as landing gear extension and retraction, verification of the environmental control system, and testing the stability augmentation system (SAS).

Since Flight 4, the focus has been on envelope expansion: slowly and methodically increasing airspeed and altitude to prepare for the first supersonic step. At each new altitude and airspeed combination, we primarily assess flutter margin and flying qualities/handling qualities.

What is the flutter margin?

Flutter is a type of aeroelastic instability. It occurs when an aircraft’s aerodynamic, inertial, and elastic forces interact to cause divergent oscillations (movement). The onset of flutter can occur very quickly, which could result in the loss of a control surface or cause other catastrophic damage to the aircraft. So, we’re very careful about it. (Think the Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse, but much faster.)

To ensure safety, we use a flutter excitation system (FES) to vibrate the aircraft in flight while we measure the structure’s response with accelerometers. The control room engineers can then calculate the damping of the structure, compare the damping to previous conditions, and extrapolate to the next condition. We are safe to proceed as long as we expect the structure will continue to damp out any oscillations. If we are unsure or think the oscillations will diverge or get bigger rather than smaller over time, then it is unsafe to continue.

What are flying qualities and handling qualities?

Flying qualities and handling qualities are the aircraft’s natural response to a disturbance. If we hit a little bump, does the airplane continue to oscillate, or does it steady out?

I use basic maneuvers to test flying qualities, such as a doublet or a step input, to excite the aircraft’s natural response and observe it. On Flight 7, we saw that the response to a pedal doublet (two small, quick pulses on each rudder pedal) resulted in an extremely lightly damped response. The airplane just kept rolling back and forth for several seconds. We did not expect this, so we changed the control laws of the Stability Augmentation System (SAS) in response and successfully corrected the issue.

I like to think of handling qualities as how easy it is to make the airplane do what I want. This is more of a subjective test and comes down to how I “feel” about the aircraft, but the flying qualities have a lot to do with my handling qualities assessment.

What is airspeed?

Both flutter and flying/handling qualities are sensitive to airspeed. When we talk about airspeed, in flight test, we’re usually referring to one of two things: Mach or Dynamic Pressure.

The Mach number expresses airspeed in relation to the local speed of sound, with Mach 0.95 meaning 95% of the speed of sound. Dynamic pressure, however, refers to the amount of pressure the airflow exerts on the aircraft. This is generally referenced in Knots Equivalent Airspeed (KEAS).

KEAS is directly proportional to the dynamic pressure but scaled to speed units that aviators can understand better. For a fixed Mach number, it will decrease with altitude. In flight test, we can choose to only vary Mach or dynamic pressure independently of one another to determine their effects on flutter margin and flying qualities.

How do you mentally prepare for a test flight?

Mental preparation for a test flight has evolved over my career. In flight school, I used to get nervous before flights, almost to the point of nausea, mostly over things I couldn’t control. That was a lot of wasted energy and agony, and fortunately, I have learned to work past it.

I still get nervous before a flight in XB-1, but I think that’s healthy. If I weren’t nervous, it would indicate I wasn’t taking it seriously enough or was ignoring the risks. My mental preparation process isn’t a defined ritual today, but I think a few things are essential.

First, my Faith has always been an important part of my preparation. I’m incredibly grateful for the abilities and opportunities God has given me, the people who have helped me along the way, and the belief that I’m not alone in the cockpit. I always say a prayer at the base of the ladder to remind myself of those things and to give credit where credit is due. My prayer isn’t always the same, but “the Astronaut’s Prayer” is usually part of it.

Preparing for the brief is also a large part of the mental preparation. Doing this forces me to think through all aspects of the flight and how I will talk about it to the rest of the team and write each aspect down. That process cements all the elements of the brief in my mind and goes a long way in making me comfortable with the plan.

Flying the simulator also gives me confidence in the plane, making the flight almost muscle memory. The simulator has been such an effective tool that it has made the flight seem practically automatic.

Watching the cockpit video from my first flight in XB-1 (Flight 2), I can see my breathing rate increase, and I take deeper breaths right before brake release. I remember feeling nervous at that point. The nerves evaporated once the wheels left the ground, and I felt right at home. That was primarily due to the time I had spent in the simulator.

Finally, consistency is valuable, not because of any superstition. Doing the same things in the same order every time makes it much easier to realize if I have forgotten something. So, I always try to follow the same routine, from packing my helmet bag to performing the preflight inspection and reviewing the checklists.